A Framework for Making Successful Technology Decisions The Steps

- Date: April 29, 2025

Jump to section

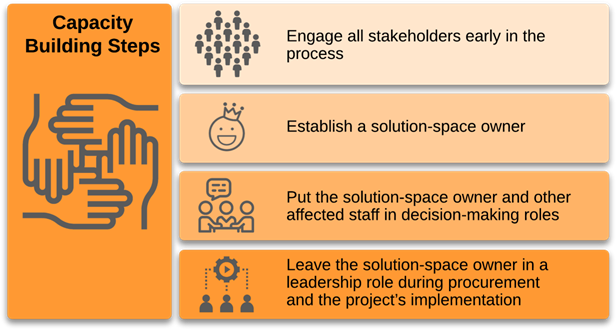

These two core concepts both support the entire process of decision-making, each using its own steps and tools to guide your team’s thinking. Whether using design thinking, systems engineering, or both, the intent of building your agency capacity is to increase your team members’ sense of ownership in the process and its success, think critically about solutions, and contribute to a complex project.

Specific steps for agency capacity-building consist of the following:

- Engage all stakeholders early in the process

- Establish a solution-space owner

- Put the solution-space owner and other affected staff in decision-making roles

- Leave the solution-space owner in a leadership role during procurement and the project’s implementation.

To ensure a coordinated approach across all parts of the project, the following organizing tools can help everyone work in concert. It’s not necessary to use all of these tools every time, but it’s important to have them available to you and your team when they can help.

Organizing tools:

- Design thinking

- Systems engineering

- Risk management matrices

- RACI matrices

Phase 1: Define and Rank Problems

One of the hazards transit agencies face is that problems don’t present themselves as clearly as a burned-out light bulb does. You have to know what problem you’re trying to solve before you start solving it. That’s the objective of phase one.

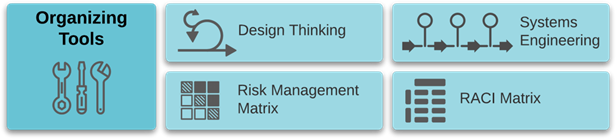

During this first phase, start by making a list of pain points across your operations, whether or not they currently relate to an automated/electronic form of technology. People know what they don’t like, making it an easy entry point that keeps attention on unmet needs. There will be time to fully inventory all the technologies that you use later. As many people in the agency as feasible should contribute to this list. Pain points are essentially observations, and they don’t have to have a particular structure or format. Then take each observation and convert it to a problem statement, which is more targeted and must meet specific criteria. Finally, you’ll evaluate each problem statement based on the risks it presents. This phase borrows from the cybersecurity-focused work of the National Institute of Standards and Technology7 and others, applying it to today’s transit context.

7 https://csrc.nist.gov/projects/risk-management/about-rmf

Cast a Wide Net to Identify Pain Points

Capacity Building Step #1: Engage all stakeholders early in the process.

The first step in identifying what isn’t working is to cast a wide net. That means including as many people from as many parts of your organization as possible in conversations about pain points. Once a pain point is identified, it’s essential to gather information from the people most affected by it; you want to be able to evaluate the severity of the situation and fully define what the problem means throughout your operations. You may even decide to go outside your organization, to access someone else’s domain expertise and/or personal experience with your services. In this paper, we won’t prescribe who should be on your team, and for simplicity’s sake, we will speak in terms of “your organization” and “your staff”, although you may be working with external partners and stakeholders, too.

Questions you can ask include:

- Practical and quantitative ones: How frequently do you encounter the pain point? How much time a week do you spend dealing with it?

- Emotional ones: What’s it like for you dealing with this issue? Does it affect your morale at work?

- Organizational ones: Who is most affected by this pain point? Why? What do you think stands in the way of a solution?

Front-line staff may not be used to thinking about other ways to get a task done (although you may be surprised!). By asking questions about their experiences, you are not only gathering information and possible solutions, but you’re also increasing your chances of success later on because this early engagement is the first step in the framework’s capacity-building process. It builds the foundation for staff to become stakeholders invested in making the eventual solutions successful.

At this point, you are focused on making observations about what isn’t working well, without emphasizing and perhaps not even discussing solutions or broader implications.

What Your Problem Statements Should Cover

After gathering information from throughout your organization, it’s time to turn your list of pain points into a list of problem statements. Problem statements have two important qualities:

Connected to mission.

Problem statements are rooted in barriers to successful service delivery, referring back to your organizational definition of what successful transit looks like. If it’s possible to establish quantitative measures of the impact of the problem, include them.

Not prescriptive.

A clear problem statement should leave you open to multiple solutions, rather than directing you immediately to a specific kind of technology purchase. An extreme example of a preconceived solution lacking a clear problem statement is “We don’t have an app. We need an app.” The lack of a specific technology is not a problem statement. It’s an accurate observation, but it doesn’t tie into what we want to accomplish for riders.

When rewriting your pain point list into problem statements, check for considerations like the ones below. You should keep asking questions (these or your own) until you have a problem statement that can be directly connected to a technological issue that is getting in the way of achieving all or part of your mission.

Because of this problem, are we:

- Falling short on any of the core expectations8 that make transit useful?

- Getting out of alignment with the agency’s approach to the ridership-coverage tradeoff?

- Feeling the effects of inefficiency?

- Suffering from growing pains?

- Stuck with aging tools that no longer work?

- Putting the safety of our staff and/or riders at risk?

- Hurting the morale of our staff?

- Facing an existential threat (“If we don’t do this, we lose relevance.”)?

Figure 3 shows examples of pain points, along with draft and final problem statements.

8 See Chapter 2 of Human Transit by Jarrett Walker. A summary of the core expectations can be found at https://humantransit.org/2011/12/outtake-on-endearing-but-useless-transit.html.

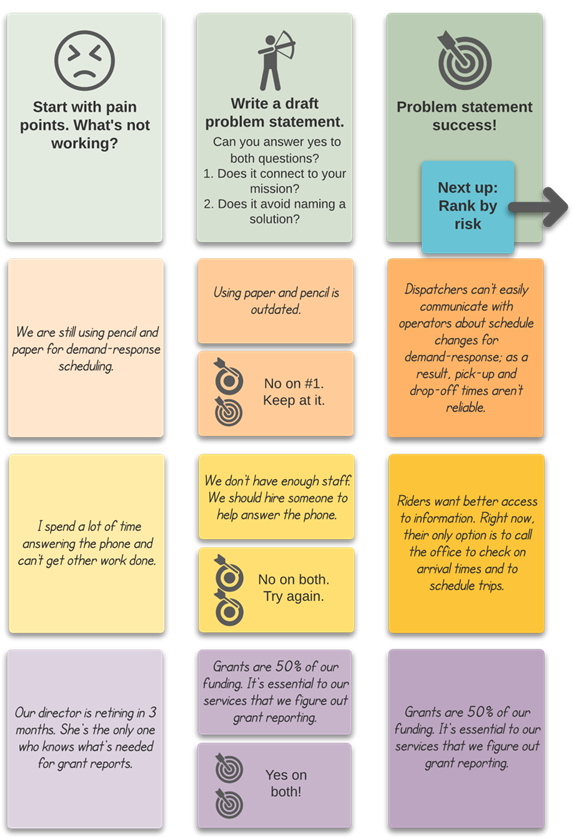

Ranking Problems by Risk

When it comes to managing risk, it’s helpful to look at two dimensions:

- What’s the level of impact of this problem/situation, especially on service reliability?

- How likely is it to occur?

This risk management matrix provides one way to organize a set of potential risks along these two dimensions.

You can place all of your problem statements within a matrix like this to help you set priorities. Your matrix will undoubtedly look different (and it should!); this example includes issues beyond technology and isn’t tied to your agency’s particular situation.

- Red: Anything that is highly likely and would have a high impact is something that you want to make sure you’re paying attention to and planning for. You’ll also want to put energy toward things that wouldn’t be terrible but would be disruptive.

- Yellow: This category is also a worthwhile area to spend time on. For instance, disaster planning needs to happen, even though disasters are infrequent. Similarly, failing computers and tablets are sure to happen and would have enough of a negative effect that you want to be ready for what to do.

- Green: These issues shouldn’t take much planning to address.

This matrix is particularly useful as a reminder to look ahead at implementation and maintenance; it’s never too early to think about these phases of a technology project.

When ranking your problem statements, it’s also helpful to be as specific and quantitative as possible when describing the costs associated with each problem. Estimates are fine, and in many cases, they’re unavoidable. Quantitative measures will come in handy later for measuring how much the final system solves the problem.

Phase 2: Develop Potential Solutions

Assemble Your Team(s)

Capacity Building Step #2: Establish a solution-space owner.

You’ve already tapped into the expertise of your organization’s staff about what isn’t working well. Now it’s time to involve your staff in exploring ways to fix what’s broken or tweak what could be better.

We suggest forming at least one team to investigate problems and possible solutions. A team should incorporate people representing as many roles and perspectives as possible. It’s okay if not everyone (or even if no one) feels confident about technology. Having a “beginner’s mind” can be helpful, because expertise sometimes results in blind spots. Coming to this process relatively unburdened by preconceived notions can be an advantage.

If you are one of the valiant information technology staff serving a small transit agency (thank you!), you are probably the only in-house technologist. Your perspectives and knowledge will be essential to this process. Being involved in a team like this will help you increase your understanding of how to present a technology issue in a way that a non-technical person can better understand. And your non-technical counterparts will likely gain a greater understanding of what makes your work challenging and valuable.

For each problem statement, establish a “solution-space owner,” who will manage the exploration process and the selection and implementation of the eventual solution. Distributing these leadership roles among staff will increase the agency’s overall capacity to make good decisions. It’s crucial to make sure these people have the time to do this work, and if a leadership role is new to them, create a supportive environment for them to ask questions about their challenges.

Understand Your Systems

Your agency is aiming to end up with a successful technology portfolio, which is essentially a collection of systems that interrelate in a thoughtful and sustainable fashion.

To understand where you’re starting from, your team should map out as many of the systems currently in place as possible, for every aspect of your operations. You might think that this should have happened earlier, prior to identifying problems. That’s certainly a reasonable thought. We put it later in the process, so your team’s first task isn’t overwhelming. It can be daunting to dig deep into the details of your operations, so we recommend beginning with pain points instead.

Consider systems in the following areas, and add others specific to your situation.

- Scheduling and dispatch

- Customer tracking

- In-vehicle technology: computer-aided dispatch and automated vehicle location (CAD/AVL); internet connectivity (routers, Wi-Fi, etc.); camera systems; stop annunciators; automatic passenger counters (APCs); headsigns; fare systems

- Reporting: for operations (for example, NTD, hours, miles, ridership) and finances

- Fleet management

- Other asset management

- Connectivity: telephony, internet at facilities, and mobile network or radio in the field

For each system, document the available budget, staffing, and existing infrastructure. It’s also a good time to assess each system’s reliability, usefulness, and time frame for mandatory replacement.

Take the time to examine the workflows for each system. These steps can be so routine that it may be hard to articulate them. Writing down each step in your current processes will help you later on, when you are evaluating the impact of a new technology on your existing workflows.

As you build this map, you’ll undoubtedly identify systems that you’d like to have, even if it’s in a vague way (“better scheduling,” for instance). You’ll also want to think about what kind of budget, staffing, and infrastructure would be needed to support these new systems. In thinking about the budget, remember that grants are great for purchasing and implementing, but your budget needs to account for the full life of any purchase. Be clear-eyed about what resources are available for long-term maintenance and staff training. At this point, you may not know enough about new technologies to forecast necessary resources accurately; that’s fine. Any information gaps can become part of your research priorities.

Build Knowledge by Casting an Even Wider Net

A solution team’s main task is to gather information that will build the agency’s collective expertise. Whether team members are working in unison or individually to build knowledge, we recommend going outside your organization to learn more.

No matter who you’re talking to, take every opportunity to ask about costs and what others are getting or accomplishing for that cost. You’ll be able to form better cost estimates as a result.

Above all, expect and plan for this stage to take time. You’re investing in this process so that you ultimately have solutions that meet your specific needs. Below, we’ve shared four potential sources of information and support.

Reach Out to Vendors, Peers, and Aggregators

You’re not alone! Even though your agency might feel unique in terms of the mix of services, funding sources, or other constraints, you have access to a large number of people who run transit agencies who have felt the same way about technology, whether that’s skeptical, reluctant, overly optimistic, or overwhelmed. Even if they haven’t solved the same problem you are trying to solve, you have peers who have gone through the process of incorporating some kind of technology to address a problem.

Getting advice and guidance from people who’ve been part of technology implementations can help you build your expertise in making technology decisions. You can do this by reaching out to peers that you know have done something similar to what you are planning, contacting knowledge aggregators like the National Center for Applied Transit Technology, National Rural Transit Assistance Program, Federal Transit Administration, National Aging and Disability Transportation Center, and your state DOT and/or issuing a Request For Information (RFI) prior to releasing a more formal Request For Proposals.

Issuing an RFI is usually not required in a procurement process. You should develop an RFI only if you see a clear need for one and if you have the capacity to implement the process. You could also take an even less formal route by contacting vendors you already know about or asking for recommendations from your network.

Whether you call it an RFI or not, this optional action has several advantages when it comes to building your expertise with technology decision-making.

- Informally gathering information: Although an RFI involves a structured request, it is substantially less formal than an RFP process. An RFI can spark conversations that are not possible once you’ve issued an RFP.

- Developing relationships: You may get RFP responses from a wider network after issuing an RFI.

- Surveying the market: By finding out more about what’s out there (from vendors and from the agencies that use these products), you are becoming a more informed consumer.

RFIs have an advantage over Requests for Qualifications (RFQs), in that an RFI is open to input from other agencies and groups like N-CATT, too. It’s helpful to hear from people who use technology as well as those who sell it. Building your expertise regarding what’s on the market and what other agencies have already done may help you refine your understanding of your problem.

Learn from Other Industries

The wide net you’re casting can also stretch outside the transit sector. Other industries have problems that are similar, if not the same, to those of transit organizations. Any industry that manages a fleet of vehicles has probably thought about in-vehicle cameras and asset management. Logistics companies, for instance, are close cousins of transit.

Going to a Conference? Map Out Your Strategy

Conferences can present a dizzying array of learning opportunities. When you’re trying to gather knowledge related to a specific problem area for your agency, it’s a good idea to have a conference game plan. Before you go, make lists of whom you want to talk to, whether that’s a hallway conversation with an agency peer or a chat at a vendor’s booth.

Have a clear research agenda. Be ready to ask vendors the questions that matter to you about their products, maintenance/support services, and overall costs. Vendors are most likely to send members of the sales team to a conference, but sometimes their engineers also attend. Regardless of who you’re talking to, your goal should be to get a good sense of their product’s capabilities, using strategic questions such as:

- What do your most successful product implementations have in common?

- Who do you think your ideal client is?

- Where does most of your business come from? (This could be in terms of geography, agency size, or type of service)

- When have you seen clients get stalled in implementing your product?

- Where do clients stumble as they use your product?

- What do you think a client should have in place before they adopt your product?

You will likely hear a lot about the strengths of their product, so much so that you may wonder if there are any flaws at all. However, as you listen to their answers, look for what they didn’t say. For instance, if they primarily serve fixed-route service providers and your primary need is for demand-response scheduling, that’s an area of potential mismatch. If you’re able to make these connections in the moment, fantastic; if you need to take some time after the fact to reflect, that gives you a starting point for a follow-up email or phone call with the vendor.

Do You Need a Consultant?

Knowing whether to bring in a consultant can be tough. How can you know if you’ll realize any return on the investment, both in terms of the contracting cost and your time? If you’re starting to think about seeking consulting support, consider reaching out to your peers or staff at technical assistance centers like N-CATT, National RTAP, NADTC, or your state DOT. These resources can provide a reality check about whether you need an ongoing outsider perspective, and they may have suggestions about where to turn.

Here are three situations where we’ve seen consulting services present clear advantages:

Significant Investment

Significant investment is required and your team is in unfamiliar or rapidly changing territory. When you are considering spending a good deal of money (you’ll need to define what constitutes “a good deal of money” for yourself) and you aren’t comfortable with the subject matter, a consultant with relevant expertise can help you learn what you need to know, so that you can spend your time and money wisely.

Problem Definition

When you and your team are unable to define a clear problem statement, a consultant can facilitate conversations to uncover needs from all stakeholders, build a shared understanding of a project’s purpose, and share experience about how other agencies have solved similar problems.

Implementation and Project Management

You may have a solid statement of what you want to accomplish, but no staff capacity to draft the RFP or oversee the implementation. Or maybe the implementation steps require technical expertise that you don’t have in-house. In these scenarios, a consultant can work from the decisions you’ve already made about the project requirements and timeline.

Though procuring consulting services can be its own painful process, the combination of industry expertise and fresh perspectives can make the difference when the path forward is unclear.

Set Priorities

As your team wraps up its knowledge-gathering activities, it’s time to review what you’ve all learned. Revisit your risk management matrix to see if your assessments have changed. Fill in anything that wasn’t previously accounted for, whether that’s a more informed cost estimate or a new risk you hadn’t thought about.

As you match possible solutions to the risks, an outline of your priorities should emerge. It may be tempting to address all the most important/highest risk areas right away, but it’s very important at this point to think about your agency’s capacity to implement. Most of the time, you’ll come out ahead by working in phases, starting with the most important or foundational elements first. Consider that unplanned staff turnover or other risks may happen, and think through the steps you’d take to mitigate these risks. Because major projects tend to touch every part of an organization, one reliable rule of thumb is to sequence them one after the other, to avoid their conflicting with one another in unexpected ways.

Comparing Your Options

At the same time that managing transit is inherently complex, small urban and rural transit occupies a small niche in the overall mobility landscape. Although we dearly want plug-and-play solutions, oftentimes, those are not currently available for our industry. As a result, we have to be exceptionally rigorous when we examine different options available to us.

Know What’s Most Important

Costs and benefits don’t always translate directly to dollars or any other quantifiable numbers. The impact of rider-facing amenities is often stated in qualitative terms, which brings a good deal of subjectivity into the picture. Your cost-benefit analysis is going to come down to saying, “This is how important x is relative to all our other concerns.” An agency strategic plan is the first place to turn for that kind of prioritization; if none is available to you, seek to align your ranking of different options with priorities that your agency has already set as much as possible.

You need to be ready to rank different options—and to be ruthless every time. This diligence will keep you focused on what’s truly most important to meeting your ultimate goal of improving the rider experience at a sustainable pace. Be sure to keep the costs and benefits of the status quo in the running as a real option so that change for change’s sake doesn’t get an implied boost in the analysis.

Take care to consider both a technology’s public visibility and its value to the service your agency already provides, and be clear about what you are trying to accomplish. Are you intent on converting non-transit riders? Are you aiming to meet the needs of an agency’s core rider population? It’s important to be explicit about your goal.

It can be an uphill struggle to prioritize investments that substantively support the rider experience when there are flashier projects that garner more attention from the non-riding public. This is especially true with technology investments. In recent years, venture capital-funded ride-hailing businesses have exerted a great deal of influence on the general public and policymakers alike, resulting in a significant overweighting of the value of mobile device apps and the types of services that rely on them.

To help them better understand the nuances of rider-centered technology investments, it may be useful to take the time to share a “Transit 101” overview for your board and other key decision- makers. This can include topics outside of technology decision making. You may want to cover issues like:

- Why service reliability matters more than almost anything else—and what can be done to increase it

- Why using smaller buses won’t save money, and where the real costs of transit are

- Why some improvements enhance agency scalability and others do not

Tell the Story of What Success and Failure Might Look Like

For many, transit technology implementations are a dry and unappealing topic. The countless obscure requirements, detailed requirements, and incremental steps often fail to stir excitement about their benefits or trigger critical thinking about how best to ensure they go well. But it doesn’t have to be that way, and the craft of storytelling can help.

Humans are natural storytellers, and throughout history, we’ve used stories and parables to drive points home more effectively than direct advice or warnings can achieve. Specifically, the future retrospective can make the best and worst of technology projects come alive for you and your stakeholders. To write future retrospectives, imagine it’s one year after the new technology was fully implemented. You and your team now have a clear view of how things went. Work together to tell the tale under two contrasting scenarios:

- Success: The project proved a resounding success, meeting or exceeding expectations.

- Failure: The project ended up being a significant disappointment or outright failure.

The goal here is not to achieve a photorealistic picture of the future. Rather, it’s to engage your storytelling powers to gain insight into the complex interactions between the strengths and weaknesses inside your organization, along with the opportunities and threats outside it. It’s a chance to bring imagination and experience together to illustrate how your team’s unique skills could rise to meet the challenges of a technology project and how past mistakes could recur if their underlying causes are not actively addressed.

This exercise can help accomplish a few key things to improve your project planning:

- It more actively engages stakeholders, both the authors and the readers of the stories, who may otherwise stay on the sidelines.

- It identifies risks more vividly, making it easier to plan countermeasures. For example, a future retrospective might include staff burnout as part of a failed project, due to no reduction in duties while working in two systems during an extended system transition period. That scenario provides a compelling reason to develop a staffing plan to reduce that risk.

- It paints a picture of what good and bad outcomes would specifically look like. This picture can then be used to devise quantitative performance measures to evaluate the project when it is completed in the real world. For example, if a future retrospective foresees a successful real-time bus arrival signage project where dispatchers are freed up from answering rider calls asking where the bus is, then that points to the importance of tracking how much time dispatchers spend doing that work.

Remember: Technology Wasn’t Necessarily Built with You in Mind

Let’s say you’ve already spent much time articulating the problem you want to solve. It’s complex, but you are convinced that the tech companies must have already accounted for everything. It’s all built-in already, so all that’s necessary is finding the right vendor to Solve All the Problems.

Well, maybe. It’s true that there is a lot of software out there that seeks to automate workflows, for instance. But every organization is different, and so you have to dig into the assumptions that the software makes about how your organization works. Earlier in the process, your team mapped out your existing workflows, and now it’s time to compare them to the workflows that were assumed during the software design process.

To get a sense of what this workflow comparison process would look like, consider what it was like for you to switch from a flip phone to a smartphone or to help someone else make that transition. You had a piece of technology that you knew how to use, even though it had its limits. Then you replaced it with one that could do everything that your flip phone could do and so much more. You needed to relearn the steps for making a call, sending a text message, saving someone’s contact information, and taking a photo, among other things. You probably moved from pushing manual buttons to a touch screen. You didn’t have the option to replicate the actions that you were used to taking to accomplish a task. You had to learn the new workflows that were built into your new phone.

The same kind of transition will be necessary for any new transit technology you adopt, but at an organizational scale. If you opt to go with an existing product, be aware that you will need to adapt to the workflows that come along with it. When you commit to a vendor, prepare for the organizational change that commitment entails. By engaging a broad cross section of your staff in the overall process, you’ll set yourself up for a greater chance of success if new workflows are necessary.

It is likely that a vendor can make adjustments for your type of operations, but that may add to the cost and complexity of your project. Like everything else, customization has its costs and benefits to weigh carefully, and you’ll need to understand the amount of necessary customization in order to make that analysis.

What Can You Commit to Maintaining?

As you look at costs and benefits, don’t forget to assess your organization’s capacity to bring the necessary resources to be successful with a solution. Of course, it’s important to think about your implementation plan and all the potential disruptions a technology transition will cause. However, the main limitation around technology is less about what we can implement. Instead, it’s what we can maintain. Talk to other agencies that use the product or products you are considering about their experiences. How much time does the specific technology you’re interested in require as far as maintenance goes? What steps are involved? Who needs to be trained and retrained? What support contracts need to be in place? Take the time to work backward from the resources that will be available to you once everything’s in place, and evaluate your ability to maintain each option you’re considering over time. If you can already foresee that one of your options will take too much time or money to maintain, cross it off your list.

A common misconception is that a new system will need less time for maintenance, or even that it will be maintenance-free. As soon as possible, confront this line of thought with a reality check. New technology is more likely to change how time is spent rather than save time. You may gain efficiency in one area of operations, but additional requirements in other areas will at least partially offset that. It’s up to you to assess whether that trade-off is worthwhile in your situation.

Term to Know: Software as a Service

As you consider your options, you may encounter the acronym SaaS (pronounced “sass”), which stands for software as a service. SaaS products represent a different method of getting access to software. In the past, software would be “locally hosted”—installed directly to your workstation and/or your on-premises server. You’d pay for the software licenses as capital expenses. The software “lived” on your computers, and whenever the software company developed a new version, you were responsible for manually loading the upgrades, probably from a disk, CD, or other physical storage device.

With SaaS, the software lives on servers at a remote data center, not on any of your hardware. It’s “web hosted”, rather than locally installed, and you access it via the internet. The software company is responsible for making sure the software on the remote server is up to date. Rather than paying a one-time purchase price, you pay a subscription fee to have access to the latest version of the software. You’ve probably seen notifications on your computer along the lines of “The system will be down from 1 a.m. to 3 a.m. on date X for a version upgrade”. The next time your computer restarts, it will have all the latest features and bug fixes for that program. No CDs required!

Chances are good that any software you purchase today will be provided under a service-based model. If you currently have locally hosted software, it’s likely that the software vendor will at some point stop providing support for it, if they haven’t already. When you make the transition to SaaS, you’ll need to consider some operational issues.

One risk with SaaS is that if your internet connection is down, that means you can’t access your software—which can paralyze scheduling and dispatch, among other critical operations. Since implementing SaaS usually results in some cost savings over locally installed software, a good use of those dollars is to build redundancy into your network, either through a system that automatically switches to a second wired connection (available in many urban areas) or to cellular service (often the only other option in rural areas).

Another risk with SaaS comes from the SaaS provider itself; their systems can go down, too. Any SaaS provider should be able to provide information about their “uptime” history and how they will communicate with you about service disruptions. These issues should also be clearly addressed in their service-level agreement (SLA), in terms of the guarantees they provide regarding uptime and the compensation given when those guarantees aren’t met.

How Well Do Existing Technologies Serve Your Needs?

After gathering information about potential solutions to your high-priority concerns, it’s time to step back and review them. This is where the two systems thinking tools explained earlier come into play.

Design thinking allows you to be flexible and iterative when considering multiple options and how they might fit together. It’s also a good method for testing out whether you can minimize the use of new technology; maybe you have a pencil-and-paper system for scheduling that’s actually working better than any electronic system would, given your situation. As a fairly open-ended process, design thinking can be difficult to use when a project involves a set budget or timeline, however.

There are cases when design thinking alone isn’t going to be enough. You’ll need additional tools if:

- You reach the conclusion that the current marketplace simply doesn’t address your problems;

- You see that your needs can only be met by chaining together a series of independently produced technologies; or

- You are coordinating across several agencies to unite different technologies in a way that should be seamless for riders.

These situations benefit from systems engineering. Whether and how much engineering to do is a key decision-point. Your team should consider the following questions carefully:

- Are there any off-the-shelf solutions?

- How much new engineering is truly needed, and why? (e.g., there’s no solution in the marketplace, required integration with legacy systems, etc.)

- What are the ways to minimize new engineering and instead rely on the prior engineering work of vendors?

- What are the mature or developing standards you can lean on?

- If the goal is to forge new ground or address an as-yet unmet technology need, who can be your strategic partners? Who are the potential peers, coordinating bodies, funders, or other players who can team with you?

Systems engineering isn’t for everyone. It requires considerable agency capacity, and it’s only worth doing if your project demands it and you can devote time and money to it.

If your task is complex enough to require systems engineering, it’s worth considering whether you want to build a solution that neighboring agencies could use to address common issues. Pooling resources can help offset some stresses and, perhaps, reduce expenses, but it requires considerable time for coordinating efforts. Asking yourself whether teaming up with your peers is a good question for your analysis; just remember that you need to take the same hard-eyed approach to assessing the associated costs and benefits.

Design thinking and systems engineering can complement each other. For example, engineered elements can be procured one by one according to an iterative master plan. The plan can then be refined after each successive piece is put into place.

Establish and Track Effective Performance Measures

Because technology projects can be so daunting, simply getting a system into place can seem like a huge success all by itself. However, using that as the sole measure of success for a project effectively makes the technology solution an end in itself, rather than a tool to serve the agency’s mission. The alternative is to use performance measures.

Quantitative performance measures are valuable in technology projects largely because, simply put, we can never assume that technology will do everything we expect it to in a transit operation setting. The overarching truth is that unexpected results are a viable possibility whenever complex systems interact with one another. This even includes getting effects opposite to the ones intended, a phenomenon called “cobra effects.” This inherent risk can leave many leaders of smaller transit agencies understandably reticent to invest in technology tools because they value the predictability that comes with their existing low-tech processes.

When well designed, quantitative performance measures reduce risk by giving early warning signs that a technology system may not be serving its purpose as expected. Is on-time performance dipping? Are more riders calling in to ask where the bus is? Are rider complaints increasing? In complex systems, problems can have many causes, so it’s not always possible to draw a direct cause-and-effect relationship using a particular measure. Still, it can be a key part of recognizing that something is off and that an investigation into root causes for subpar performance is needed.

Earlier in this framework, we recommended looking for candidate performance measures when developing pain points, problem statements, possible solutions, and future retrospectives. Before implementing a solution, it’s critical to select one or more of those measures based on how well they align with the solution’s goals and ease of collection. Collecting baseline data should also begin before the solution is rolled out to reliably determine whether it has the desired effect.

For example, an agency may decide to add driver tablets to their existing dispatching solution after hearing about operational challenges from dispatchers and riders about how hard it is to know where the bus is. A future retrospective for failure imagined that drivers wouldn’t receive enough training or support to learn how to use the tablets effectively. As a result, the person leading the implementation started collecting data three months before the implementation started:

- Dispatchers started keeping a daily tick sheet for tracking the number of riders asking about bus location.

- A rider survey was conducted with a focus on perceptions of service reliability and how riders accessed service information. Resources were set aside to repeat the survey 3, 6, and 12 months after project completion.

- Brief weekly driver surveys were established, collecting 1-to-5 ratings of satisfaction with project execution, with space to provide reasons for the rating.

Use Standards and Advocate for Greater Interoperability

Having data in standard formats is incredibly powerful; it allows us to share information across agencies. One of the most important applications of data standards is trip planners that pull in information from multiple transit providers. Thanks to the General Transit Feed Specification (the oldest and most mature standard in transit) and its extension, GTFS-flex (which deals with demand-response transit), independent agencies can present a seamless interface to riders for trip planning.

What does this mean for your decision-making process? You should always ask vendors about their products’ compliance with standards. Emphasizing standards and interoperability between engineered components allows for gradually adjusting how pieces connect or swapping out of components. It’s not quite a plug-and-play solution, but standards will help you get closer to that.

In the case of a mature and public-facing standard such as the GTFS, it’s important to require that a product support the standard in a high-quality way. For example, it’s essential to confirm that a product’s GTFS output will represent your agency’s services accurately when they appear in Google Maps or other tools.

GTFS and GTFS-flex are powerful, but they don’t cover everything that we deal with in transit. Many other standards are in development. You don’t have to become an expert in all these standards (although if that’s appealing to you, go for it!). The most important thing you can do is bring an awareness of standards to your decision-making process. As you talk with vendors, you can help nudge them to be thinking ahead about these proto-standards and how they should be incorporating them in future versions of their products.

Leaders: Think in Trade-Offs and Be Ready to Make Hard Decisions

If you trace back the path of many successful technology decisions, you’ll often find that an agency leader had to make a hard decision, say, forcing two agencies to merge or scrapping an entire fare scheme. These decisions can be necessary in order to make a technology solution (and the ultimate goal of improvements for riders) viable. More often than not, these leaders have had to think about trade-offs. Sometimes that analysis involves comparing significant initial effort versus a long-term payoff.

Making decisions at this scale takes leadership. You must create a vision and lead your team and external stakeholders through that change. Above all, you can’t just think, “Oh, we just need to buy this technology, and that’s it. Our problems will be solved. The technology will take care of everything.” Whatever technology we pursue for our agencies is part of a much more complex system, and we need strong leadership to help the people who are also part of that system embrace the changes new technology can require.

Phase 3: Procuring

Capacity Building Step #3 Put the solution-space owner and other affected staff in decision-making roles

Procurements can be painful. Here are some practices to help make it easier.

- Assemble a review committee that includes the solution-space owner and other affected staff, to continue the commitment to agency capacity building.

- Explore areas for contracting where the vendor’s revenue model aligns with agency outcomes. For example, can you provide bonuses or other incentives if clearly defined quantitative performance measures are met, such as cost savings, improved on-time performance, etc.?

- Look into whether your solution can be procured under the cost threshold for a formal procurement. Due to the pricing structure of SaaS subscriptions, you may be able to stay below the formal procurement bar for new software.

- For elements you’ve engineered, lay out all your work: requirements, designs, phasing.

- For problems for which you’re seeking an already engineered solution, don’t over-prescribe. Instead, focus on communicating as simply as possible your conditions, the problems you’re trying to solve, and the outcomes you expect.

Phase 4: Implementation and Maintenance

Capacity Building Step #4 Leave the solution-space owner in a leadership role during implementation

As with procurement, the successful implementation of a technology project is a topic worthy of further consideration. You’ll need to develop a plan for getting the solution in place, tracking its performance, and maintaining it for the long haul. The specifics will vary widely depending on what you’re implementing. Some considerations apply universally, however.

- For the sake of continuity, the solution-space owner should retain a leadership role during implementation and maintenance.

- If you’ve chosen to use a vendor-engineered solution, commit to and follow through with that process.

- Sustain your capacity-building efforts by clarifying roles and responsibilities. Outline roles for implementation and ongoing maintenance across the organization according to whether someone is responsible, accountable, consulted, or informed (RACI). These roles can be summed up in a RACI matrix.9

- To the extent the solution involves the disruption of established roles, the engagement of top-level leadership is essential.

Your work doesn’t end with implementation, however. In the same way that you pay careful attention to ongoing maintenance needs of your fleet vehicles, you also have to develop a technology maintenance mindset. The workings of technology may feel invisible, but they do still need to be tended. You’ve committed a lot of time and money to getting these systems in place, and you’ll want to keep them in good working order. Again, the details will vary depending on what technologies you’re using. As needed, ask for help in developing a maintenance plan from peers at other agencies, your IT department, your vendors, or outside consultants, as appropriate.

9 https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Responsibility_assignment_matrix