Engaging Frontline Employees in Adopting New Transit Technologies Apprenticeships for New Transit Technologies

- Date: April 13, 2023

Jump to section

4.1 Opening

Apprenticeship programs are a method that transit agencies can apply to achieve goals such as recruiting new staff effectively, ensuring that staff have critical knowledge and skills, and supporting a solid career base for employees. Apprenticeships are one way the transit industry can ensure it has a sustainable talent pipeline; however, the practice has not been universally adopted at transit agencies. In the US, they have predominantly been most common within the construction industry; apprenticeships have traditionally not been as common in the US in general when compared with countries such as Germany, for example. Apprenticeship programs are an attractive option for transit agencies striving for jobs that have the potential to become careers with greater long-term opportunities—providing a base for employee engagement and helping to retain staff.

Although a comprehensive resource that elucidates the current status of apprenticeship programs in the US transit industry is not currently publicly available, a report called Building an Apprenticeship and Training System for Maintenance Occupations in the American Transit Industry was published by the Transportation Learning Center (TLC) in 2009 that helps shed light on the topic. The researchers of the report were able to confirm through surveys that there were fifteen known “self-described” apprenticeship programs (of any type, not only for maintenance occupations) at transit agencies in the US. It is explained in the TLC report that the term “self-described” is applied because the programs are “in various stages of development” and are “exhibiting a wide range of quality and approaches,” going further to say, “Most transit apprenticeship programs were jointly administered through employer-union partnerships. Many programs were registered with state apprenticeship agencies or the US Department of Labor… The isolation and independence of individual transit agencies has led to a great deal of local variation among transit apprenticeships. Transit agencies train workers based on the specific needs, equipment, organizational structure, and idiosyncratic culture of their agency. The result is that the term transit apprenticeship can refer to a variety of programs with often widely dissimilar aims and practices.”

There are two general ways that a transit agency could go about addressing the educational requirements for new transit technologies with an apprenticeship program—adding transit technology-specific content to an existing program or working toward having a new apprenticeship program. A new apprenticeship program could either incorporate transit technology-specific content within a broader topic (e.g., a “coach operator” apprenticeship that includes ZEB-specific details) or enable the apprentice to specialize in a new transit technology through the apprenticeship program (such as a “ZEB mechanic” apprenticeship). There are resources available that may help a transit agency with any of these paths.

- In August 2021, the FTA announced the creation of the Transit Workforce Center (TWC), funded through a $5 million cooperative agreement with the International Transportation Learning Center (ITLC). Explained about the TWC, it “is the first FTA-funded technical assistance center to directly support public transit workforce development. Its mission is to help transit agencies recruit, hire, train, and retain a diverse workforce needed now and in the future.” This, and other efforts, comprise FTA’s Workforce Development Initiative. It should be noted that the TLC and the ITLC are the same organization, going by different names at different points in time.

- On the TWC webpage of the ITLC’s website, it is mentioned that the activities of the TWC fall into two programs, one with “technical assistance activities within and for transit agencies that promote more effective and efficient training of frontline workers involved in public transportation maintenance and operations” and another that involves implementing “technical assistance activities through collaborative partnerships between transit agency management and labor, including apprenticeships.”

- Also explained on the ITLC’s website, a part of the TWC’s activities will involve overseeing the American Transit Training and Apprenticeship Innovators Network (ATTAIN). ITLC provides further detail, “Membership in ATTAIN provides agencies interested in implementing an apprenticeship with continuous support from the TWC and the opportunity to learn from each other through peer dialogue. This exchange of ideas and experiences complements the individual technical assistance that ATTAIN members will receive from the TWC to help agencies learn and apply best practices for registered apprenticeship.”

- There have been grants in the past in support of apprenticeships in the US transit industry, such as those provided through the FTA’s Innovative Transit Workforce Development Program (ITWDP) which consisted of a series of projects in 2011, 2012, and 2015 totaling $20 million for approximately 40 grants.

The Santa Clara Valley Transit Authority’s (VTA) partnership with Mission College and Amalgamated Transit Union (ATU) Local 265 was brought to the National Center for Applied Transit Technology’s (N-CATT) attention by a representative from the ATU who had direct experience with the partnership. This partnership is referenced throughout this chapter in order to contextualize points being made with a well-documented and successful apprenticeship program already in place.

An apprenticeship program that is focused on new transit technologies, which the VTA example is not, would have been ideal to include in this Guidebook. That was not possible, since interviews with a representative of the ATU revealed that such apprenticeship programs are currently in development, but not yet in place. More details on this are provided in section 4.8. In summary, the VTA example is provided to thoroughly explain and illustrate how an agency could go about establishing an apprenticeship program in general, and this information can be applied to any type of apprenticeship program—regardless of if it is focused on new transit technologies or not. The VTA example is not intended to provide an exhaustive list of activities, but instead a general framework to consider when setting up a new partnership-based apprenticeship program. Behind the Wheel: A Case Study of Mission College and Santa Clara Valley Transportation Authority’s Coach Operator Apprenticeship Program, published in 2019 and prepared for the Foundation for California Community Colleges, has provided the majority of detailed information in this chapter; citations are in place for other information sources when applicable.

4.3 How apprenticeships can help facilitate career pathways

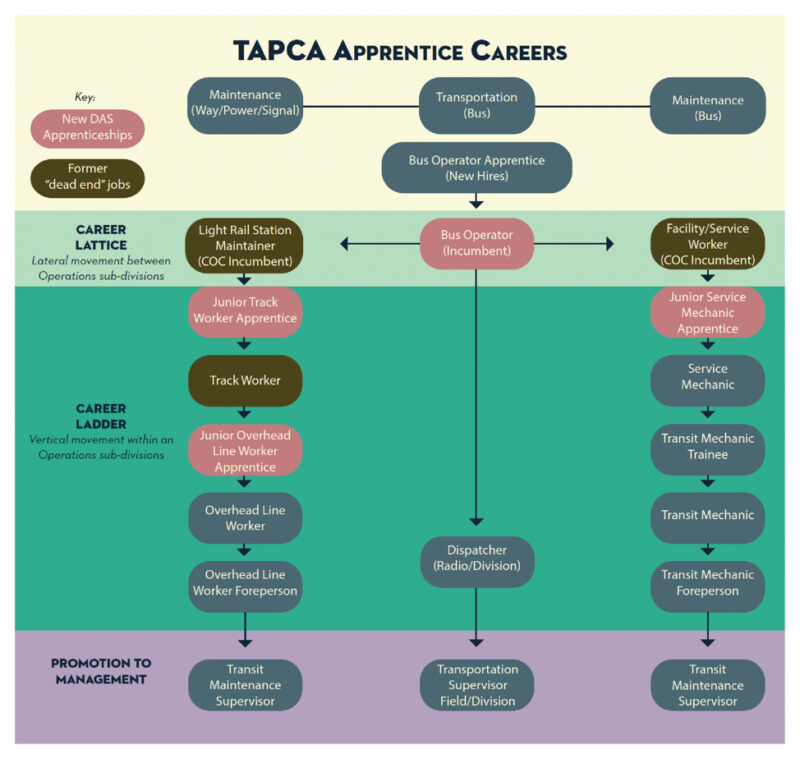

In section 4.2, the concepts of “career lattices” and “career ladders” were mentioned along with figure 4, which helps to illustrate these concepts. The Equity from the Frontline report sheds light on how these concepts, and their accompanying apprenticeships, were developed and the impact they’ve had on individual staff members, “The apprenticeships have turned what was once a dead-end position into a professional gateway.”

When VTA realized it was in need of more staff, experienced bus mechanics and facility/service workers (i.e., staff members who help with fueling vehicles, cleaning them, etc.) suggested developing a career path from facility/service work positions to bus mechanic positions. As a part of developing this path, the “Mechanic Helper” pilot program was put in place. Mike Hursh, former VTA Chief Operating Officer, explains in the Equity from the Frontline report that “we took vacant, mechanic positions and built an apprenticeship program for fuel island workers around them. We then used vacant fuel island positions to fill from the community. To provide access to union jobs with benefits, career jobs.”

Ten “Mechanic Helpers” were recruited from the facility and service worker pool in 2008. Eligibility and selection are explained further in Equity from the Frontline, “a worker must have completed Evergreen College’s Automotive Systems 102 (employer reimbursement for C or higher), passed a mechanical aptitude test, and demonstrated good job attendance and performance. Selection was then based upon seniority.” The apprenticeship program transitioned from “Mechanic Helpers” to the “Service Mechanic” title (the current TAPCA iteration) between 2008 and 2016.

Carl Hart, a program graduate, said in Equity from the Frontline “Workers once stuck in entry-level cleaning positions express the deepest appreciation for… the mentorship program, and the apprenticeship career ladder. People can now see that it’s possible to move from the Fuel Island into a more professional position.” When VTA began this program, the only ways to become a bus mechanic were mainly through technical schools (outside of VTA), the military, or auto dealerships/repair shops. VTA was able to chart a path through the agency from less-skilled positions to skilled maintenance positions and change the status quo dramatically.

The personal story of Eliseo Acosta, a service mechanic apprenticeship graduate, is shared in Equity from the Frontline. “Eliseo became a service worker because it was an opportunity to work for the VTA, an agency known for family-sustaining, long-term careers. He soon experienced the low morale and stagnation of working on the fuel island… cleaning and fueling coaches on the 6:00 pm to 2:30 am shift did not provide the skills or opportunity to progress.” Describing his early experience, Acosta explained “It’s hard to see a future on the fuel island. It’s not the kind of job you can see yourself doing long-term.” Once he met the eligibility requirements, he joined the first cohort of the Service Mechanic apprenticeship, which was then considered a pilot project. All ten apprentices in his cohort made it through the program. Acosta explains in Equity from the Frontline, “If there was no Mechanic Helper Apprenticeship, I probably would have left the company. We got paid to go to school for a year at our previous union wage. We also kept our seniority. That was really important.”

4.4 Partnerships with educational and organized labor partners

Educational partners, such as community colleges and trade schools, often use apprenticeships as a way for their students to access the talent pipeline into certain industries and with specific employers such as VTA. Unions also sometimes play a support role in apprenticeships.

In Building an Apprenticeship and Training System for Maintenance Occupations in the American Transit Industry, it is stated that “American apprenticeship programs are sponsored either unilaterally by employers alone or jointly by unions and employers. In joint programs, apprenticeship is often organized under terms of the collective bargaining agreement that specify the training wages, apprentice-worker ratios, and financing of apprenticeship. Training is commonly financed from a dedicated training trust fund into which employers contribute a few cents per every hour of labor hired. The local Joint Apprenticeship and Training Committee (JATC), composed of representatives of unions and employers in equal numbers, administers the training program and use of the dedicated training fund, and makes decisions concerning program requirements, curriculum, and admissions, and monitors the performance and advancement of apprentices.”

The TAPCA Program, which began in 2016, was built atop previous efforts among the three partners: VTA, ATU Local 265, and Mission College. An earlier effort between VTA and ATU Local 265, the Joint Workforce Investment (JWI), was launched in 2006. VTA had identified multiple workforce challenges that led the agency to realize a new approach was needed. As mentioned in the Behind the Wheel report, these challenges included “pending large-scale retirements, recruiting and retention challenges in key positions, ongoing integration of new technologies, worker health and safety concerns, and the need to help VTA employees better prepare for the public service aspects of their jobs.” The JWI had three main goals including professionalizing key occupations, improving the talent pipeline for critical positions, and increasing the “engagement, well-being, satisfaction, and retention” of workers.

A JWI mentoring and professional development program was launched in 2007. Foundational concepts of the TAPCA program, such as “career lattices” and “career ladders,” have their roots in the JWI. Building on the details shared in section 4.3, employees with jobs cleaning and fueling vehicles were able to move into entry-level service mechanic positions in 2008 through JWI’s “Career Ladders Training Project.” The educational program consisted of credit-based training, on-the-job training, and peer mentoring—all of which were paid work. An additional career path was supported; workers who were already entry-level service mechanics were able to advance into full transit mechanic positions, moving into a higher salary with a greater skill level. The JWI also helped to produce a coach operator training program, a precursor to the Coach Operator Apprenticeship of the TAPCA program.

The partnership between VTA and Mission College developed over time as well. Initially, Mission College was brought into the JWI partnership in order to help create what was called the “JWI Academy,” a program with a set of courses with the aim of fostering leadership skills in field-level workers—culminating in a certificate of achievement. In 2012, Mission College reached out to VTA expressing interest in potentially setting up apprenticeships. As the relationship evolved, Mission College realized that VTA’s size (2,100 employees) and its level of demand for newly-trained employees presented an opportunity to have a single program with multiple apprenticeship options (i.e., something similar what the TAPCA program became), all supporting the transit industry which had earlier been identified as a key priority for the state and region. As mentioned in the Behind the Wheel report, by 2015 Mission College had “…secured one of 46 American Apprenticeship Initiative grants awarded by the US DOL to build apprenticeship programs in key sectors. This federal grant helped Mission College apprenticeship champions get their arms around registered apprenticeship as a concept and a process. It also laid a foundation for the development of TAPCA… In particular, it familiarized college program staff and VTA with the process of establishing an apprenticeship program—including documenting needs, identifying occupations, building and registering programs, implementing training, and tracking processes.”

4.5 Funding opportunities and registering apprenticeships

Section 4.1 mentioned past grants funded through FTA’s Innovative Transit Workforce Development Program (ITWDP); the Workforce Innovation and Opportunity Act (WIOA) has been another significant source of federal funding.[1] Some funding requires the participation of partners with a transit agency—both from unions and from an educational institution, for instance.

The four apprenticeships within the TAPCA program were initially funded through the California Apprenticeship Initiative (CAI) grant program in 2016. This grant was awarded to Mission College in partnership with VTA and ATU Local 265 and supported registering the apprenticeships with California’s Division of Apprenticeship Standards (DAS) in 2016. The apprenticeships were registered under the American Apprenticeship Initiative with the US Department of Labor’s (US DOL) Office of Apprenticeship (OA) in 2015.

An Eno Center for Transportation article from 2019, “Training and Apprenticeships to Address Transit Workforce Gaps,” provides guidance on how to go about registering an apprenticeship. “There are several steps needed to achieve registered apprenticeship status. Like all Department of Labor (DOL) sponsored apprenticeships, the program is designed with flexibility, allowing agencies to benefit from the national guidelines but tailoring them to address individual agency needs and resources. First, top labor and management representatives from the agency must commit to the program. A joint apprenticeship committee (JAC) is formed with equal representation of labor and management to develop local standards that determine how the apprentice program is structured (i.e., apprentice and mentor selection process, work hours, wage progression, etc.) and the training program’s content (i.e., work process schedule, OJT, and classroom coordination, etc.). The final step is to formally register with DOL and launch the program.”

4.6 How apprenticeships work

Apprenticeships typically have a classroom-based period to gain skills and an on-the-job period to practice those skills, often supplemented by a mentorship program. Apprentices in the transit industry typically become both agency employee and college student simultaneously and tend to be paid during the apprenticeship period.

The Building an Apprenticeship and Training System for Maintenance Occupations in the American Transit Industry report provides an overview of how apprenticeship programs often work. “Most registered apprenticeship programs are time-based, although competency-based programs, or hybrids of competency-based and time-based programs have been approved. Apprentices are paid according to a progressively increasing schedule of wages as their skills improve. The term of time-based apprenticeships ranges from one to six years, but three or four years is the most common. Apprentices are expected to complete 2000 hours of supervised on-the-job training and at least 144 hours of related in-class instruction per year… Classes are normally taught by advanced journey-level skilled workers or supervisors who also work with the trade.”

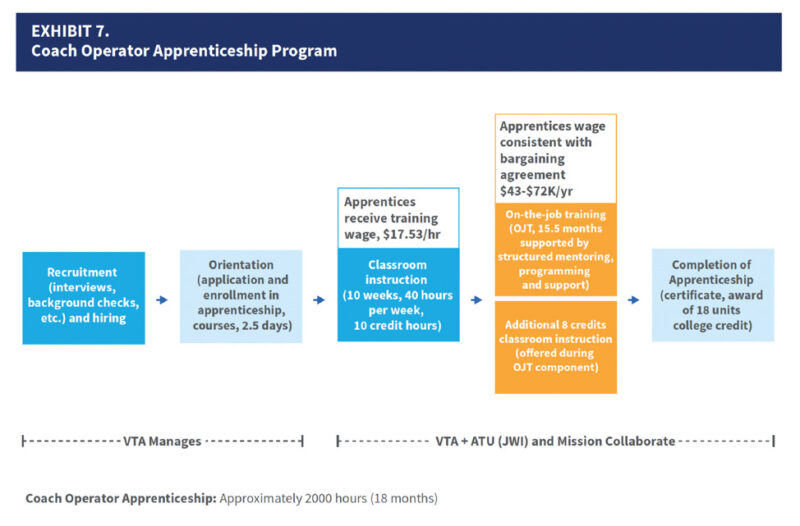

VTA’s Coach Operator Apprenticeship, part of the TAPCA program and used as the example in sections 4.6.1-4.6.5, includes 10 weeks of full-time classroom training followed by 15.5 months of on-the-job training for approximately 18 months in total. These details are illustrated in the Behind the Wheel report as shown in figure 5. Mentoring is integrated throughout the on-the-job training component. The apprenticeship program is the only way to become a new coach operator at VTA.

4.6.1 Recruitment

Recruitment is handled by VTA a few times a year through highly-advertised open application periods. Interviews, background checks, and other internal processes are completed by VTA. After being selected for the program, the new staff members join a two-and-a-half-day orientation program, also managed by VTA. Apprentices complete their Mission College admission applications during orientation, since they need to be enrolled as students in order to begin. Among other topics, the orientation introduces them to the JWI and the mentorship part of the program, which begins during the on-the-job training period. As further detailed in the Equity from the Frontline report, “VTA’s human resources department handles recruitment of new operators. Selection is highly competitive with the agency receiving over six thousand applications in the one week per year that the position is open. One in seven applicants receives an interview and practical exam on a coach (i.e., bus).”

4.6.2 Classroom training

Following orientation, they go right into the 10 weeks of classroom training, which is when they officially become both VTA employees and Mission College students and begin receiving an hourly wage ($17.53 per hour as of December 2018). The courses are taught at VTA facilities by VTA instructors; all instructors are approved by Mission College. At the end of the 10 weeks, apprentices have 10 hours of academic credit. In general, these new recruits are also new VTA employees, but in some cases, they are current VTA employees who have decided to transfer to a new occupation.

4.6.3 On-the-job training

Soon after the completion of classroom training, the on-the-job training component begins. One of the first activities apprentices take part in is a series of “ride-alongs” with their mentors, so they can become accustomed to what happens on the bus without being the driver. Their pay goes up during this 15.5-month period (to $43,000–$72,000 annually as of December 2018). They are paid a standard annual wage in line with the collective bargaining agreement.

4.6.4 Mentoring

Throughout the on-the-job training component, apprentices benefit from mentoring. This takes the form of coaching while the apprentice is operating the bus, guidance on how to best manage interactions with the public, and advising them on other matters such as handling night shifts and “split shifts” (i.e., having a shift with a non-paid break in the middle of the shift). Experienced VTA coach operators serve as mentors after applying and completing training in order to do so.

4.6.5 Certifications

In order to gain approvals and register the coach operator apprenticeship, along with the other TAPCA apprenticeships, the curriculum was submitted for approval at Mission College and registered with the US DOL in 2015 as well as with the California DAS in 2016. At completion, each apprentice receives a certificate of achievement from Mission College, outlining college credentials, and “journeyman certificates” from DAS and US DOL. The ATU, in particular, has emphasized the importance of these certificates to recognize these occupations as professions while encouraging apprentices to pursue additional higher education and training.

4.6.6 Administrative aspects

The partnership group is interested in making a number of administrative improvements to the TAPCA program including:

- Mission College application and course registration – It has been noted that the complexity of the application process can be cumbersome for first-time college attendees, which the apprentices tend to be. In addition, the current registration processes do not easily make an exception for apprentices to avoid the payment of registration fees, which they are exempt from per state regulation. To address both of these concerns in the short-term, Mission College and VTA have a paper registration process they facilitate with hands-on help during the orientation process. This gives them more control, enabling them to explain to apprentices how to complete certain sections and how to avoid the payment of unnecessary fees.

- Hiring VTA employees as faculty – The instructors of the classroom component are VTA employees, but they must be officially hired by Mission College as well—a requirement for the apprentices to earn college credit. Typically, being a college instructor would require a certain level of education and certain types of college credit, which even the most experienced employees at VTA may not have. In its first year, 2016, it was difficult to gain college approval for the instructors. Mission College has since changed the criteria required to become an instructor and anticipates these changes will make it easier for the program to secure instructors.

- Data and reporting processes – Reporting is required for California’s Division of Apprenticeship Standards (DAS), the California Apprenticeship Initiative (CAI) grant program, the American Apprenticeship Initiative grant program, and Mission College. The data that are required differ among the various entities, although there is some overlap, and there is a wide variety of required data formatting. The type of information being sought after often relates to apprenticeship program inputs such as how much time the apprentices spend in training/on the job and outcomes such as skills gained and other achievements. The lack of coordination or standards among these processes, involving multiple data entry and reporting requirements, results in a significant administrative burden, both for Mission College and VTA.

4.7 Specific benefits of apprenticeships

The Equity from the Frontline report outlines specific benefits of apprenticeships to transit agencies that should be taken into account, based on the experience of VTA.

- Assists in gaining reliable, highly-skilled, and motivated staff – Maurice Beard, a VTA Bus Training Supervisor, explains, “…eleven years into program, the biggest piece is trust. JWI has helped immensely with the competition for labor. We used to wait forever to get some positions filled such as overhead line worker. When you look at the numbers—morale, retention rate, stress, sick time— that is the benefit to the employer. Now management can rely on something. We rely on the benefits that the apprenticeship provides on the job.”

- Helps with reduced absenteeism and retention – Tai Lam, a Mechanic Helper Apprentice, says “Not just the worker has the benefit, VTA has the benefit too. It creates a sense of belonging. People are not going to go anywhere.” The authors of the report explain further, “VTA’s willingness to work differently has yielded significant benefits. Apprenticeship’s professionalized training and mentoring is evident on the road and in the maintenance bay. Absenteeism is less of a problem when people feel good at their job. VTA learned this lesson when a lack of resources placed the mentorship program on hold for a year. The agency experienced a return to high levels of absenteeism and complaints.”

- Achieves multiple needs simultaneously – The authors of the report describe the range of benefits, “The Coach Operator and Service Mechanic apprenticeships have become models for simultaneously addressing increased transit demand, deployment of high technology ‘green’ transit vehicles, impending massive workforce retirements, and the transit incumbent workforce with limited career access, training gaps, and low morale.”

4.8 Status of apprenticeships for ZEBs

A representative of the ATU reported there are approximately five known transit agencies in the US that are in the process of creating apprenticeships for mechanics specialized in ZEB technologies, and as mentioned in section 3.6, IndyGo is one of them.

Also notable regarding educational paths, Rio Hondo College in Whittier, California stands out as an example of a college that offers an Alternative Fuels Technology program[1] consisting of two different degree options, “Electric Vehicle and Fuel Cell Technology Technician” and “Alternative Fuels and Advanced Transportation Technology.” Although this program is not targeted specifically at coach vehicles or public transit buses, the description on the program’s webpage notes that employers in the transit industry are among the employers of past graduates, “Local employers seek out our students when they need automotive service technicians with Electric/Fuel cell vehicle skills. Students who complete the automotive program should have no trouble finding a job as an Alternative Fuels technician, service writer or even a service manager at dealerships, independent repair shops, parts stores or even start their own business! Our graduates are currently working at Proterra Electric Bus, LA Metro Transit, Los Angeles Department of Water and Power Fleet Technicians, and even Space-EX Technicians.”