New Software Adoption for Small Transit Agencies Chapter 1, Step 1: Set the Software Scope

- Date: February 18, 2022

Jump to section

This chapter breaks down the process of setting the software scope into three activities. For these activities, as well as all the other activities explained in this Guidebook, an agency should identify a primary staff member who is responsible for the entire software adoption process from start to finish—a software adoption process lead. They would lead all the activities, from Step 1 through Step 4. Some software adoption efforts end up having difficulties because the agency was unaware that certain activities needed to be completed, or because there was no single point of contact. Having at least one staff member who understands all the parts and how they should come together will reduce the risk of an important activity falling through the cracks.

The lead does not need to come from a software development or information technology background. The most important skill sets and knowledge the lead should have include:

Transit operations knowledge

They should have a solid understanding of how the software would be used by the agency staff and by the public, as well as which groups in particular would use the software.

Software benefits awareness

They should be able to clearly communicate with staff and the public about why the software would be useful and how it would improve operations and/or the user experience.

Organizational skills

They should know the basics of project management, how to plan for large scale projects with many parts, and understand they are responsible for bringing all the parts together. They should be someone who can work with a wide range of people to reach a common goal.

“Key takeaways” are provided at the end of each chapter to help orient the software adoption process lead toward the most critical activities.

Step 1a. Clarify the Software’s Purpose

Clarifying the purpose of the software involves identifying which software type is needed. In general, when beginning the process of identifying which software type is the most applicable to a transit agency’s needs, two situations are common. For some internal needs, it is clear to staff which software type is required, or if multiple types are required. For example, if an agency is starting a demand-responsive service for the first time, and they have decided that it will be agency-operated as opposed to a fully turnkey service, they are aware they will need a DRT software system. In this situation, the software’s purpose is clear; the agency needs a DRT technology platform in order to operate new DRT service.

For other internal needs, it may be unclear what is needed exactly, and in such cases, the agency may need to first explore their options. For reference, the software types of focus for this Guidebook are shown below. For further information, refer to the “Guidebook Focus Areas and Software Types” section of the Guidebook’s Introduction and Background Information as well as the “Software Functional Types for Small Transit Systems” section of Chapter 3.

In this situation, an agency may want to consider ways of pinpointing the type, or types of software that are most needed. The N-CATT white paper, a “Framework for Making Successful Technology Decisions,” provides detailed instructions on ways to navigate this situation.6 The Framework encourages readers to think about technology needs holistically and consider the full realm of what might be needed, even if that means considering multiple types of software within a broader technology portfolio. Since the Guidebook focuses on a narrower category of technology, software only, the results of the suggested Framework process may expand beyond software. In fact, such results could be helpful in the longer term, because the agency would have greater clarity into all the types of technology that are needed—and how they should work together to suit the agency’s needs.

The Framework encourages a few methods in the first phase of activity,7 such as:

Defining and ranking problems

It is suggested to focus first on what problems the agency faces in the form of identifying “pain points.”

Creating problem statements

This takes the problems from general observations to a more specific statement that is targeted. Each statement should connect to the transit agency’s mission and avoid naming a solution.

Evaluating problem statements based on risk

This method involves assessing the potential level of impact of the problem on core needs of the transit agency, such as service reliability, as well as its likelihood of happening. The assessed impact level and likelihood can then be mapped onto a risk management matrix for comparison.

In the second phase of activity,8 solutions are identified. This phase can be connected to the software types of focus for the Guidebook in order to match software types, as potential partial or complete solutions, to the problems. It is possible that the activities mentioned in the Framework result in a set of technology-related solutions that don’t involve any software, but if the need for specific types of software is revealed, the Framework information can be used within this Guidebook step to clarify the purpose of the software product.

If an agency applies these methods early on in the software adoption effort, they may have a solid base for not only a complete technology portfolio, but also technology plans or roadmaps that connect elements of the portfolio with time-based phases to break down when certain elements may be implemented.

6 National Center for Applied Transit Technology. A Framework for Making Successful Technology Decisions. Available at: https://n-catt.org/tech-uni- versity/a-framework-for-making-successful-technology-decisions/ as of February 10, 2021.

7 National Center for Applied Transit Technology. A Framework for Making Successful Technology Decisions, pp.13-18. Available at: https://n-catt. org/tech-university/a-framework-for-making-successful-technology-deci-sions/ as of February 10, 2021.

8 National Center for Applied Transit Technology. A Framework for Making Successful Technology Decisions, pp.18-30. Available at: https://n-catt. org/tech-university/a-framework-for-making-successful-technology-deci-sions/ as of February 10, 2021.

Step 1b. Identify General Software Connectivity Needs

If, while clarifying the purpose of the software, an agency determines that it will need to adopt more than one type of software, then the connectivity needs of the new software will also need to be identified. Further, new software always connects into an agency’s broader software ecosystem, and exploring this as well can help with the adoption of new software. An agency should make sure it understands all existing software that may have some connection, however limited, with the new software. At the same time, it should look ahead to future planned software that may also have some connection.

For the purposes of this Guidebook, a software “connection” is defined broadly. On one end of the spectrum, a connection could mean that a staff member uses both types of software in their daily work. Perhaps although they use both, they don’t necessarily need them to exchange data or directly connect. Nonetheless, in this example, it should be noted that the two software platforms contribute to common, or related, work tasks. On the other end of the spectrum, a connection means that there is a direct relationship between the two, such that data must be exchanged between them or that they perform functions directly connected to each other. This side of the spectrum involves software that is interoperable.

Conceptually, the term “connectivity” could also be used in reference to Internet connectivity, which is facilitated by connecting mobile devices (e.g., smart phones and tablets) to the Internet via wireless location-based routers (i.e., wifi) and via cellular data that covers wide geographic areas. For the purposes of this Guidebook chapter, “connectivity” refers to software connectivity, not Internet connectivity.

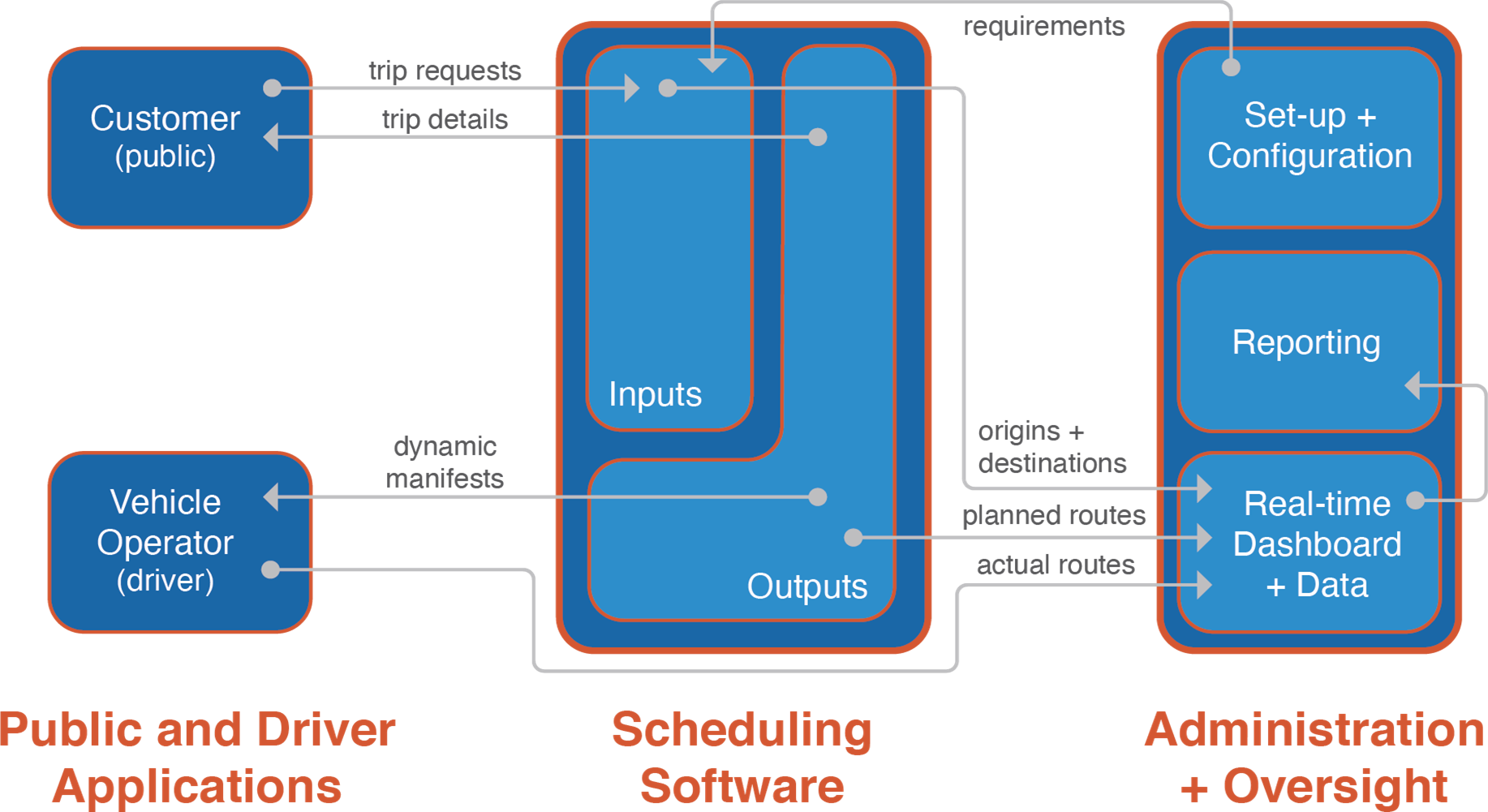

An example of interoperable software, on-demand transit operations software, is shown below. This software, or software platform, is comprised of multiple pieces of software, each with a high level of interoperability with one another. There are many connectivity needs that exist. The customer inputs their trip request into the customer app, which is sent to the scheduling software; this is one connection that is needed. Once a manifest is created, the details are sent to the vehicle operator, who is using an app for navigation purposes; this is another key connection. All the information on the trip request and final trip delivery details are available as data to be leveraged in the reporting module or the data dashboard—an additional needed connection. In this way, all the components are designed as parts of a whole that work together to achieve a variety of critical results.

In the example just cited, the software vendor provides a comprehensive, integrated solution to all of the needs of an on-demand transit service, as would typically be the case of such software that has become available in the past 2 or 3 years. But it can also be the case that an agency has older software that is less comprehensive and integrated, and needs to be augmented in certain ways, or has a much simpler DRT service that is perceived not to require the same level of comprehensiveness and integration as what is now the state of the art. Even in such cases, it is important for the agency to have a solid understanding of the connection needs of its software—current and future—so that if the agency does pursue additional software products then it will consider them functioning well with one another. If it does not think comprehensively about how the different software elements should work together, the agency staff may find themselves in a situation where they continue to need to handle things manually, costing the agency time and money— contributing to a lack of productivity and efficiency in its internal operations.

While software interoperability can help an agency with its services internally, it also impacts passengers. Mobility as a Service (MaaS), for example, stresses the importance of making trip planning, booking, and payment easier on the passenger through interoperability. In this sense, interoperability can mean that one app supports multiple functions seamlessly such as trip planning, booking, and payment—each function would be interoperable with the other. On the other hand, some level of interoperability could potentially be accomplished through multiple apps or software that are designed to work together.

Interoperability between separate software or apps can either be custom-built or achieved by using an intermediate method such as an application programming interface (API).9 When a software developer knows in advance that two software products should interoperate, it is possible to build in what is needed to facilitate the interoperability as the software is being designed, written, and tested. However, it is far more typical for a software to instead have an API built that works as a sort of appendage to the software in support of connecting that software with another software. APIs have the potential to facilitate the connection of one software product with countless other software products.

By listing all of the existing, new, and future planned software and thinking through the spectrum of connections that should ideally exist between them, an agency can clarify its connectivity needs. Within Step 1, only a general connectivity understanding is needed. Software interoperability and APIs are covered in further detail under “Inter-Operable Software Considerations: A Short Discourse” within the “Software Functional Types for Small Transit Systems” section of Chapter 3.

9 InfoWorld. What is an API? Application programming interfaces explained. Available at: https://www.infoworld.com/article/3269878/ what-is-an-api-application-programming-interfaces-explained.html as of February 10, 2021.

Step 1c. Anticipate Resources to Apply to Software Adoption

Software adoption can benefit from an early look into an agency’s resources to consider what can be brought to bear on various aspects of the adoption process. Resources include, at a minimum, financial resources, staff resources, assets, and collaborator resources.

An agency can create an inventory of all its anticipated resources early on in the software adoption effort in order to be prepared for later Guidebook steps. Chapter 3 includes details of the procurement process and the deployment of financial resources. Chapter 4 refers to resource-dependent tasks such as training staff members and maintaining the software.

Key Takeaways

Clarify the software’s purpose by connecting the transit agency’s needs with the corresponding software type or types. For situations when it is unclear which software type is needed, apply the methods provided in the N-CATT white paper, a “Framework for Making Successful Technology Decisions,” to explore an agency’s technology portfolio more broadly.

Identify general connectivity needs by listing all of the existing and future planned software that will have a relationship, even a loose one, with the new software type or types. The details of the connections are not needed during Step 1, only the understanding that some sort of connection should exist.

Anticipate resources to apply to software adoption by creating an inventory of all an agency’s potential resources, within the agency and from partner organizations.

Illustrative Project

10 United States Census Bureau. Quick Facts. Available at: https://www.census.gov/quickfacts/ as of February 10, 2021.

11 Florida Commission for the Transportation Disadvantaged. About us. Available at: https://ctd.fdot.gov/aboutus.htm as of February 10, 2021.