On Demand Transit and Microtransit: Where and Why What Are On-Demand Transit and Microtransit?

- Date: October 31, 2023

Introduction

When thinking of public transit, people often think of traditional fixed-route services, such as buses and trains that pick riders up at a stop or station according to a pre-determined schedule. But how do we provide transit service to people in less dense and less walkable communities—or to any location at less busy times of day—where—or when— fixed-route transit is not operationally appropriate or financially practical to provide? Many small and rural transit agencies facing this challenge have employed demand-response transit service models, including microtransit.

Although demand in rural and small urban areas may be low, agencies strive to provide transit services that best serve their communities. Agencies seek to connect even the most remote, low-density areas to destinations in their service area, aiming to expand opportunities through mobility for as many people as possible. Additionally, specialized transit serves as a lifeline for people with disabilities, older adults, and people without access to a personal vehicle. For these purposes, demand-response transit provides a less expensive, more effective, and more attractive service than fixed-route transit. However, demand-response trips must often be booked days, if not weeks, in advance due to large, low-density service areas and limited operating resources.

The traditional way to connect demand-response customers with a vehicle is the telephone. Customers are usually required to call to book a trip, generally at least the day before the trip, and agencies have to staff a call center for reservation intake and dispatchers. In recent years, online platforms and one-call/one-click services have become another common booking option. At their simplest, one-call or one-click services enable customers to make one phone call or search one website to receive information on transportation services, while more advanced services allow customers to schedule, receive confirmation, and even pay for rides.

Interest in increasing the convenience and efficiency of general public demand-response services has grown in the past decade as advances in technology and the reduction of technologies’ costs have made the provision of flexible and more customer-centric public transportation more feasible. One driving force in this process was Transportation Network Companies (TNCs), such as Uber and Lyft, and their technological advancements in dispatching, routing, and communication. TNCs, also known as ridesourcing or ride-hailing providers, have shaped a new transportation era allowing customers to use a smartphone application (app) to plan, request, and pay for trips, as well as track a vehicle to their curb in real-time.

Key Terms

Presenting key terms associated with on-demand transit is crucial to contextualizing and defining microtransit. New terms have emerged as technological advancements have enhanced how demand-response transit is delivered. Table 1 identifies some terms associated with new and on-demand mobility.

Table 1: New Terms Associated With On-Demand Transit

| Type | Definition |

| Mobility On Demand (MOD) | On-demand transportation leverages transit networks and operations, real-time data, connected travelers, and cooperative Intelligent Transportation Systems (ITS) to provide “on-demand” mobility, which means that mobility supply and demand from riders are managed through real-time communications. |

| Shared Used Mobility | The umbrella term for shared transportation services and resources shared among users, either concurrently or one after another. For this Guidebook, shared mobility refers to public transit demand-response transit and microtransit. |

| Transportation Network Companies (TNC) | A company that provides transportation services using a technology-enabled platform that connects customers with drivers using their personal vehicles, on-demand, real-time, and curb-to-curb service. |

| Ridesourcing/Ride (e)-hailing | A type of ridesharing that allows customers requesting a ride for one or two passengers to be paired in real-time with others traveling along a similar route. |

| Ridesplitting | Defined as adding passengers to a private trip in which driver and passengers share a destination. The arrangement provides additional transportation options for riders while allowing drivers to fill otherwise empty seats in their vehicles. |

| Geo-Fenced Zone (GFZ) | The use of location-based navigation technology, such as global positioning system (GPS) technology, to create virtual geographic borders and define specific actions to take place at or within those borders. |

| First Mile/Last Mile (FM/LM) | The beginning or end of an individual transit trip. When walking access to and from a transit stop or station is inconvenient or impossible, other solutions can improve access to transit. |

What is Demand-Response Transit?

Demand-response transit has had a long-standing presence in small urban and rural markets, serving as a lifeline connector for the public, but particularly for older adults and people with disabilities.

Like most on-demand services, microtransit can be seen as an evolution of existing modes enabled by technology. Therefore, this chapter defines microtransit by first exploring what demand-response transit is. Demand–response transit service is not a new concept. Some transit agencies started providing more flexible services, such as fixed-route

deviation and point deviation services, in the 1980s. However, the general public tends to associate demand–response public transit service with paratransit service provided to assist people with disabilities.

According to the FTA, demand-response transit is any public transit service that transports individuals without fixed routes or fixed schedules, except temporarily to satisfy a special need. Typically, a demand-response vehicle may be dispatched to pick up several passengers at different pick-up points before taking them to their respective destinations and may even be interrupted en route to these destinations to pick up other passengers. Table 2 lists and defines the most common types of demand-response transit service types variations.

Table 2: Common Demand-Response Transit Service Types

| Type | Definition |

| Route Deviation | Vehicles operate on a regular schedule along a defined path, with or without marked bus stops, deviating to serve demand-responsive requests. |

| Point Deviation | Vehicles serve demand-responsive requests within a zone and serve a limited number of stops within the zone without any regular path between the stops. |

| Demand Response Connector | Vehicles operate in demand-responsive mode within a zone, with one or more scheduled transfer points that connect with a fixed-route network. |

| Request Stop | Vehicles operate in fixed-route, fixed-schedule mode and serve a limited number of undefined stops along the route in response to passenger requests. |

| Flexible Route Segments | Vehicles operate in conventional fixed-route, fixed-schedule mode switching to demand-responsive operation for a limited portion of the route. |

| Zone Route | Vehicles operate in demand-responsive mode along a corridor with established departure and arrival times at one or more endpoints in the zone. |

Source: TCRP Synthesis 53: Operational Experiences with Flexible Transit Services

Over the years, small urban and rural providers have deployed demand-response transit for similar reasons, typically using smaller vehicles (sedan, van, or cutaway bus) to supply the curb-to-curb service. The primary purpose is to supply public transit coverage to residents and maximize efficiency by offering as-needed services to less densely populated areas. In rural areas, demand-responsive services are a safety net for transit-dependent populations and, in most cases, the only public transportation service available.

Another reason agencies deploy demand-response services is to supply door-to-door transportation to people with disabilities. Under the Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA) of 1990, public entities are mandated to supply complementary paratransit service equivalent to the fixed-route network. Some agencies supply deviated fixed-route bus services to satisfy ADA requirements. In these cases, the operator maneuvers from the published route alignment to pick up and drop off ADA paratransit customers. While older adults are not a federally protected class, agencies tend to provide the same service parameters to adults 65 and older.

In many rural areas, the point deviation type of demand-responsive transit—the traditional dial-a-ride service—is the only transit alternative available for the general public. However, these demand-response trips must be pre-booked, may have wide pick-up and drop-off windows, and users have access to little information on the trip status or wait times. In addition, scheduling and routing for traditional dial-a-ride services are often done by hand, and these services tend to suffer from low productivity. Technology, particularly on-demand transit technology, offers the potential for transit agencies to serve lower-density areas more efficiently while enhancing the customer experience.

What is Smartphone-Enabled On-Demand Transportation?

Technological advancements in software and communications changed how on-demand transportation services are delivered. In 2009, Uber became the first TNC to offer on-demand ridesourcing/ride(e)-hailing services via a GPS-equipped smartphone in real-time, as well as using web browsers. Uber’s business model quickly galvanized an enterprise of peer-to-peer on-demand e-hailing firms (Lyft has emerged as the prevalent competitor). Based on the e-hailing appeal, in 2014, Uber and Lyft introduced ride-splitting into the shared-use mobility arena. Influenced by the demand-response transit model and building upon the ridesourcing model, ride-splitting pairs customers with similar trip origins and destinations in real-time for a shared ride with the potential for multiple stops.

Transportation Network Companies (Uber and Lyft) changed how people access transportation, allowing customers to use a smartphone app to plan, request, pay, and track an on-demand vehicle curb-to-curb in real-time.

Capitalizing on the novel service delivery model, public transit operators started cultivating partnerships with TNCs and subsidizing passengers’ Uber and Lyft trips within pre-determined parameters. In 2016, Pinellas Suncoast Transit Agency (PSTA) and Uber developed the nation’s first transit agency-TNC partnership. To address the FM/LM conundrum in low-density service areas, the PSTA pays the first $5 of customers’ Uber trips to/from bus stops within designated zones. In another example, the Town of Innisfil, Ontario, developed a similar partnership with Uber and subsidized residents’ UberPool trips to/from designated public hubs within the township’s limits. TNCs changed how public transit agencies partnered with the private sector, allowing each industry to leverage its strong capabilities to improve the customer experience.

What is Microtransit?

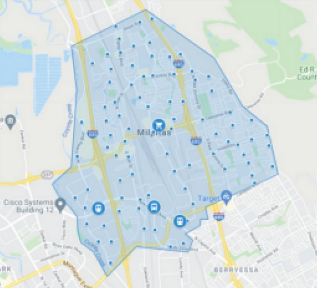

The FTA defines microtransit as an IT-enabled multi-passenger transportation service that serves passengers on dynamically generated routes and may expect passengers to make their way to and from common pick-up or drop-off points. The ability to use a smartphone app to plan, request, pay, and track curb-to-curb on-demand transportation transformed people’s travel choices. Capitalizing on the technological advancements in the smartphone, private technology-based companies introduced microtransit into the shared-use arena. Microtransit combines elements of the demand-response transit model with the private TNC model, offering passengers on-demand or pre-booked curb-to-curb service. Algorithms are then used to crowdsource customers along dynamic routes and schedules within a designated GFZ, commonly referred simply as a zone, offering the capability to shift between flex routing and on-demand scheduling. While the service model is not entirely new, the service delivery model enhances the customer experience.

Microtransit is emerging as an on-demand service that aims to fill in gaps between traditional fixed-route bus and ride-hailing to serve areas efficiently where traditional transit service is not suitable. Because microtransit often resembles existing demand responsive transit modes or supplements fixed-route service and combines aspects of TNCs, Figure 1 provides an overall picture of where these various modes fall in a matrix of public and private and scheduled and on-demand ranges. Due to a variety of service delivery types and modes, it is hard to pinpoint microtransit in such a matrix. However, parallels between microtransit and traditional demand-responsive transit and overlap with TNC shared trips can be seen, as well as microtransit’s position on a scale of public and private and on-demand and scheduled services.

Figure 1: Traditional (Red) and New Mobility (Yellow) Modes

In 2014, the privately operated technology-based company Bridj (which is no longer in business) coined the term microtransit, becoming the first to supply on-demand transit in real-time via a smartphone app. Bridj launched services in Boston, MA, and Washington, DC, serving as a peak period service to connect commuters from low-density suburban communities with the central business district. In 2016, Oakland, California-based Alameda Contra Costa Transit District became one of the first public transit agencies to experiment with microtransit. The microtransit pilot replaced low-performing fixed-route bus service in a suburban low-density community and served as an FM/LM connector to a nearby transit facility. The following year, the city of Arlington, Texas, partnered with the private tech-based company Via and replaced its fixed-route service with microtransit in a GFZ. Based on the program’s success, in 2021, the microtransit program expanded to operate citywide, connecting the suburban residents in low-density and low-demand neighborhoods with activity centers.

In more recent years, microtransit has gained momentum in small urban and rural environments. In 2020, the City of Wilson was awarded an FTA Accelerating Innovative Mobility (AIM) Grant to test microtransit services. The City launched its microtransit program RIDE, which completely replaced the existing transit system, expanded coverage to previously unreachable areas, and significantly reduced riders’ wait times. The Southeastern Association of State Highway and Transportation Officials awarded the City of Wilson America’s Transportation Award for “Best Use of Innovation and Technology” for using microtransit to improve access for its residents. In a similar rural microtransit program, Wayne County, Ohio, launched a countywide microtransit program to connect rural residents with nearby city centers. The service was implemented to connect residents without access to a vehicle in the sprawling 555 square miles region comprised primarily of farmlands and villages with the cities in the county. These examples and others explored in-depth in Chapter 2 show that microtransit’s delivery model has allowed public transit agencies to optimize service levels to match demand in small urban and rural markets.

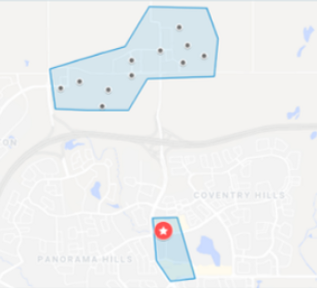

Microtransit services across the country can be organized under three common service delivery types. These types are defined based on agencies’ goals and needs and balance service flexibility and efficiency. Figure 2 identifies and defines the three most typical micromobility service delivery types. Still, agencies can work with technology providers to customize zone designs based on goals and objectives. For example, a zone can be corridor-based where pick-ups and drop-offs must be along a specific corridor (typically used when the microtransit service replaces an existing fixed-route bus route) or hub-based with rides provided between specific hubs or stops within a zone.

Figure 2: Service Delivery Types

| Zone-Based Point-to-Point

Enables unrestricted travel between two points within a designated zone (GFZ). Depending on the rider type, riders can be picked up and dropped off at either flex stops, curbside, or doorsteps. |

|

| First Mile/Last Mile

Enables restricted travel to or from a particular point of interest. Riders are picked up at a flex stop or another location within a zone and can only go to a single or a small number of defined stops, usually a transit center or transit station. |

|

| Hub-Spoke

Enables unrestricted travel between two points within a designated zone but prioritizes select popular destinations, such as transit centers, medical facilities, or shopping malls. This hybrid approach results in longer wait and onboard times for riders traveling door-to-door or from flex stop to flex stop. |

|

Sourece: RisdeCo

Service Delivery Models

In addition to service types, microtransit can be operated in a wide variety of partnership configurations. Different types of partnerships reflect agencies’ capital and operational needs. For example, a transit agency can partner with a microtransit service provider to provide any or all of the technology, vehicles, drivers, maintenance, and operations management, according to the agencies’ specific needs. However, the private partner’s provision of technology is generally common to all these arrangements. Figure 3 shows how these partnerships can be grouped into two main service delivery models.

Figure 3: Microtransit Partnerships Models

Model 1: Publicly Regulated and Operated Microtransit – Software as a Service

With this model, the public entity enters a partnership with a private technology-based company to develop the vehicle onboard driver software and/or a customer-facing smartphone app. Most commonly, an agency deploys the private partner’s technology on their agency-owned and operated vehicles retrofitted with onboard technology. This model is also known as software as a service (SaaS). However, a variation on that most basic arrangement, more common to human services transportation, can be with private-sector technology, public agency vehicles, and non-profit agency drivers. Yet another arrangement is private sector technology and drivers with public agency vehicles.

Model 2: Publicly Regulated and Privately Operated Microtransit – Turnkey

Like Model 1, with Model 2, the transit agency also enters a partnership with a private technology-based company. In this model, also known as the turnkey model, the contracted company provides the technology but also supplies the vehicles and drivers. It is also possible to enter into two separate contracts: one with a technology provider and one with a private operator.

Microtransit Benefits and Use Cases

Originally designed to complement and augment the backbone of public transit networks, microtransit has allowed agencies to provide flexible transportation that is convenient and efficient without significant investments in infrastructure. As a result, customers are provided with on-demand curb-to-curb service, reliable and potentially shorter wait times, reduced travel times, and better FM/LM connections. From the transit agency perspective, reasons for integrating a microtransit service option include:

- New or expanded coverage, providing transit in previously underserved areas

- Expanded service hours or days of the week

- Providing rural mobility more effectively and efficiently

- Providing FM/LM connection to fixed-route services

- Replacing underperforming fixed-route services

- Upgrading/supplementing ADA paratransit offerings

- Reducing call center volume

- Enhancing data processing and analytics.

Previous Research

Well-documented research has examined small urban and rural transit agencies’ experiences with demand-response transit. The Transportation Research Board (TRB) Transit Cooperative Research Program (TCRP) Synthesis 53: Operational Experiences with Flexible Transit Services is a relevant report that documents agencies’ experience with demand-response transit serving the general public in small cities, low-density suburban municipalities, and rural areas. These agencies also use the service model to supply specialized services for people with disabilities. TCRP Synthesis 76: Integration of Paratransit and Fixed-Route Transit Services complemented that study, finding that in addition to supplying service in small urban and rural areas, transit providers used demand-response transit as a feeder service for people with disabilities.

The TCRP Report 140: A Guide for Planning and Operating Flexible Public Transportation Services, a follow-up study, provided an updated comprehensive review of transit agencies’ experiences with demand-response transit. First, the report presented a framework and decision-making matrix for small urban and rural transit providers when considering demand-response transit services, including population and employment densities, trip purpose, and clientele served. The report then identified steps for implementing a demand-response transit to include analyzing existing conditions, obtaining community input, planning and scheduling the service, determining capital needs, and marketing the services. The report concluded with identifying some best use cases for demand-response services:

- Reducing the costs of full demand-response services in rural areas where passengers frequent common destinations such as medical centers, senior citizen centers, or shopping centers.

- Eliminating the need to operate ADA-complementary paratransit in a specific geographic area or systemwide if an agency chooses to eliminate fixed-route services in those areas.

- Introducing public transportation for residents not served by regular fixed-route service by offering convenient connections to frequent fixed-route buses or fixed-guideway systems.

A few studies have identified the impact of TNCs on public transit and how the private tech industry changed how people access transportation. TCRP Report 188: Shared Mobility and the Transformation of Public Transit examined the relationship between public transportation (demand-responsive transit and complementary ADA paratransit) and new shared modes to include TNCs and microtransit. One finding from the report was that public transit customers were attracted to TNCs because of the convenience of using a smartphone to book and pay for the trip and tracking the vehicle to the pick-up location within minutes. Building upon the report, TCRP Report 196: Private Transit: Existing Services and Emerging Directions found that public transit customers were switching to private on-demand e-hailing services because of shorter wait times and faster travel. A University of California Davis study, Disruptive Transportation: The Adoption, Utilization, and Impacts of Ride-Hailing in the United States, confirmed that the e-hailing appeal was growing in popularity. The report also found that while e-hailing services were primarily used in dense urban environments, there was increasing usage in low-density suburban landscapes.

More recent research examined public transit providers’ experience with microtransit. TCRP Synthesis 141: Microtransit or General Public Demand-Response Transit Services: State of the Practice is the first federal sponsored research publication exploring how public transit agencies incorporate smartphone-enabled transit in operational practice. The report found that with the rapid evolution and decreasing cost of technology, all types of transit providers are piloting microtransit programs in low-density areas as a potential low-cost FM/LM solution. Despite its relatively high cost per trip, microtransit provided through private contractors is less expensive than serving low-demand areas with fixed routes. Microtransit also has the potential to minimize expensive ADA trips due to more convenient opportunities for customers to make reservations on a real-time basis (or short time windows) rather than the day before their trip.

In another report, Spectrum of Public Transit Operations: From Fixed Route to Microtransit, the authors attempted to understand better approaches needed to address challenges encountered in the successful implementation of public transit operations, particularly regarding flexible operations such as microtransit. The report found that while demand-response transit has plenty of potential in providing efficient and viable transport service in suburban and rural areas, the successful implementation of such services requires overcoming a range of barriers to include technological, financial, integration, shortage of vehicles, safety, reliability, demand uncertainty, and performance evaluation measures faced by existing flexible transport services, especially in rural environments.

In the recently published TCRP Synthesis 154: Innovative Practices for Transit Planning at Small to Mid-Sized Agencies, the researchers conducted surveys and case studies of innovative service model approaches in small and mid-sized public transit agencies. The report identified prevalent challenges faced by those agencies to include declining ridership, demographic shifts, FM/LM transportation, changes in land use, changes in regulations, service design, funding challenges, service delivery, and technology changes for fixed-route buses, flex routes, and demand-responsive transit services. Based on survey responses, to address these issues, agencies were deploying microtransit to fill gaps in service and as an FM/LM connector to other transit service or activity centers. The report also identified lessons from case studies for public agencies to consider when developing and implementing a microtransit program. Key findings were:

- Getting buy-in. It is critical that decision-makers, partners, the public, and other stakeholders are versed in the service delivery model.

- Developing and maintaining relationships. To build trust, transit agencies should interact with elected officials and decision-makers. They also can interact with partners to create opportunities to team up and share resources and knowledge.

- Involving multiple transit agency staff. Transit agencies should involve multiple transit agency departments and staff in developing solutions to transit planning challenges.

- Making full use of the resources available. In the age of technology, there is an abundance of resources available online, in which most are free, that provide technical assistance, educational opportunities, and guidance on federal, state, and private funding sources.

- Developing a technology implementation plan. Based on the case studies, the report suggests developing a phased and multidisciplinary technology implementation plan.

- Allowing time for the service to mature. Microtransit is a new service model that is evolving, and agencies are continuing to learn benefits and challenges. As such, transit providers shall plan to modify services as lessons are learned.

- Focus on the customer. With the new microtransit model, agencies should focus on learning their customer needs and tailoring the service to accommodate their customers.

While microtransit is in an infancy stage, research to date found that technological advancements are allowing small urban and rural agencies to optimize demand-responsive services to improve efficiency and effectiveness and enhance the customer experience.

Key Takeaways

This first chapter sets the stage for the Guidebook by defining microtransit and contextualizing it in the demand-response transit landscape. Key takeaways are:

- Demand-response transit has had a long-standing presence in small urban and rural markets, connecting the public, older adults, and people with disabilities within the community and urban areas.

- Smartphone-enabled on-demand transportation was influenced by TNCs (Uber and Lyft), which changed how people access transportation by allowing customers to use a smartphone app to plan, request, pay, and track an on-demand vehicle curb-to-curb in real-time.

- Microtransit combines elements of the demand-response transit model and TNC model, allowing people to use a smartphone app to access on-demand (or pre-booked) transit services.

For agencies looking into microtransit as a transit solution for their service area, literature covering recent deployment of microtransit suggests:

- Agencies seeking to test microtransit need to prioritize customers’ needs ahead of the novelty of new technology and think critically about designing, developing, and implementing a pilot that puts the customer first.

- Agencies should utilize a contracting mechanism that empowers those most familiar with the pilot to make quick decisions outside of the agency’s standard processes in order to be able to apply lessons learned during pilots quickly.

- Agencies should prioritize the public interest in contracts with technology vendors, ensuring data sharing agreements that allow agencies data access and ownership.

- The success or failure of the application should be determined based on performance metrics that go beyond ridership changes and farebox recovery, such as improved mobility, increased safety, and enhanced customer experience.

- Agencies should establish their goals up-front and work with potential technology vendors to design a microtransit project within those parameters.

- Agencies should invest in robust marketing and outreach to ensure that all current and potential customers understand how to use the service.