Even where the ingredients exist to make a micromobility program succeed, there are a range of factors from costs to governance that will impact whether implementation is feasible. For small urban, rural, and tribal communities looking to implement micromobility, the challenges may seem seem insurmountable. Fortunately, micromobility is not one-size-fits all. There are a range of approaches and strategies that can be used to create micromobility programs. The ideal type of program is often shaped by the needs of the community being served.

4.1 Where Does Micromobility Succeed?

It is important for communities, especially smaller ones, to understand their market for micromobility before pursuing a program. A micromobility program does not necessarily make sense in every location and context. Various factors influence whether a micromobility system will succeed.

- Population and employment density is a key predictor of micromobility demand. As with any form of shared transportation, people are more likely to use the service if they live close to it. While density is concentrated in big cities, smaller communities have had success implementing bikeshare on places like main streets, historic districts, and college campuses where a high density of potential riders congregate.

- Mixed-use land uses are another factor that influences micromobility demand. Locations where there are a range of destination types driving demand at different times of day are going to be more successful for micromobility than a place where demand has distinct peaks and valleys. A good example might be a corporate campus versus a college campus. Even if both are of the same size, the corporate campus will likely generate a flow of people into the campus in the morning and an outflow in the afternoon. Alternatively, a college campus sees student and staff come and go at all hours of the day. Travel demand occurring at the same time can overtax the system and mean it ultimately serves fewer people; a bicycle ridden all day will serve more trips than one only used to bike in one direction in the morning and the opposite direction in the afternoon.

- Average trip length may also dictate whether micromobility is feasible. As mentioned in Section 2, Primer on Micromobility, micromobility trips are typically under three miles. If a transit provider is trying to improve access between destinations greater than three miles apart, micromobility may be a poor solution. In 2019, INRIX Research used data from 50 million anonymous car trips and found that almost half of the car trips made in the most congested metropolitan areas in the United States were less than three miles (INRIX 2019).

- Tourist and leisure destinations are a key attractor of micromobility trips. There are several programs built around a particular attraction. For example, Valentine, Nebraska may have what is the most rural micromobility program in the nation. The one-station system is located beside a popular recreation trail, with users renting bikes to travel out and back. Visitors to the town and trail represent the bulk of ridership according to an interview with program staff.

- Infrastructure is key to micromobility. People need a safe and comfortable route to ride. Several small systems are built around local bicycle facilities like trails. Access to bike lanes, sidewalks, and trails all can contribute to higher system ridership and increased safety for riders.

In addition to the community characteristics, micromobility systems are shaped by who is using the program. Some systems primarily serve out-of-town visitors, others are used by local residents for day-to-day travel. A few systems are restricted to a specific group (employees or college students). Similarly, systems can serve a variety of trip types, from leisure and exercise-related trips to commute trips. While some systems can sustain themselves solely on one type of rider (e.g., a recreation focused system beside a major attraction), most successful programs regardless of size depend on a mix of trips to generate demand.

New micromobility technology is changing where programs are viable. An e-bike pilot program in Aspen found that when using e-bikes, riders arrived an average of four minutes faster to their destinations than conventional bikes while encouraging riders to travel uphill and inducing longer-distance rides (WE-cycle 2020). On a larger scale, e-bikes could open bikeshare use to a wider type of ridership (e.g., seniors for whom a traditional bike is not feasible). The report also notes the potential for electrified rides to replace 40 percent of car trips that are two miles or less in length if the network is expanded. One interviewee for this project recommended that every jurisdiction planning on implementing bikeshare include e-bikes.

4.2 Ownership and Governance

There are several types of micromobility business models that clarify which parties own the micromobility equipment, such as the vehicles and docking stations, and who is responsible for operating and managing a program. Under some models, jurisdictions may lease or buy micromobility vehicles and equipment from vendors and operate the system on their own. Table 3 outlines the types of program ownership and operation arrangements that exist today.

| Program Owner | Program Operator |

|

|

TCRP Synthesis 132: Public Transit and Bikesharing examined three models: non-profit owned and operated; privately owned and operated; and publicly owned and operated by a third party (TCRP 2018). Based on a literature review and interviews, publicly owned and operated systems appear to be the most common model for bikeshare systems in small urban and rural settings. There are limited examples of scooters in these contexts. Additional information is available in TCRP Research Report 230.

4.2.1 Operations and Ownership Considerations Specific to Small Urban and Rural Communities

In an interview for this guidebook, a vendor described their key considerations when pursuing a new market and determining operating and management models. Vendors focus primarily on locations that could support a viable and sustainable financial business model. Systems in large cities benefit from high population densities and associated ridership with user fees that contribute to financing the system. Since smaller and rural locations do not have high levels of density, public funding or private sponsorships may be required to make a system viable.

Collaborative partnerships with volunteers (such as bike non-profits) and in-kind donations can help reduce some costs associated with operating a micromobility program. Many of the smaller systems surveyed as part of this guidebook rely on volunteers and donations. A key concern for programs is sustaining support over the long-term; volunteers may leave their position or fundraising may become more challenging as time goes on.

Finally, small systems face challenges in right-sizing staff and resources. A small system will not warrant a full-time employee nor require the same robust IT systems as a large program (e.g., enterprise resource management software). Another consideration is the level of staff expertise – servicing a small system requires staff to be experts in all parts of the business (operations, maintenance, etc.), whereas large systems require dedicated, specialized staff (e.g., staff that only focuses on maintenance). Outsourcing some functions (e.g., partnering with a local bike shop for maintenance instead of having dedicated maintenance staff or relying on in-kind donations such as storage or office space) can help smaller systems make their business work with limited resources.

WE-cycle opened in Aspen, Colorado in 2013 and expanded to Basalt, Colorado in 2016. The non-profit is funded through a public private partnership. Founding partners and private donors provided the initial funding for capital infrastructure, and operations are funded by local jurisdictions (WE-cycle 2022). In 2017, the Roaring Fork Transportation Authority (RFTA) entered into a five-year partnership with WE-cycle and agreed to commit $100,000 annually (subject annual approval) (Stroud 2017). The system’s 2019 annual report provides data on how the bikeshare addresses first mile and last mile connections to transit, with 35 percent of morning checkouts coming from bus rapid transit stops and 50 percent of WE-cycle rides originating or ending at a Bus Rapid Transit (BRT) stop (WE-cycle 2020). Users can checkout bikes and see real-time bus schedules through the Transit app. Users with an RFTA bus pass can ride the bus and check out bikes with a single card. The system added e-bikes and installed the first two solar-powered bikeshare charging stations in the United States in 2021 (Herbert, Solar E-bike Stations Are the Future We Need 2021). WE-cycle has also actively engaged the local Spanish-speaking population through its dedicated Movimiento en Bici program.

Community-led bike lending libraries are another option for small and rural areas. Public libraries, local jurisdictions, or non-profits can run these systems with either donated or purchased bikes. Allen County, Kansas started one of the first of these libraries with initial funding from Blue Cross Blue Shield of Kansas (NCHRP 2019). The Commerce City branch of the Anythink Library in Commerce City, Colorado started a bike library program with 30 bikes that were donated after Denver’s bikeshare system ceased operations. The former vendor for the Denver bikeshare contacted Commerce City, but the City did not have the capacity to operate a program. Thanks to a good relationship between the City and the library, the City approached Anythink to ask whether the branch library could implement a bike program.

Anythink went to work on drafting a business plan that identified stakeholders; a project timeline; goals; a budget; a project plan (that identified required research, funding, and setup and support needs); and identified potential risks (including customer injuries; customer dissatisfaction with bike quality; and lost/stolen bicycles). The library worked closely with the city to obtain permits for a new concrete pad, a shed to store the bicycles, extending the fence around the library, and to obtain additional grant funding to pay for the improvements as well as locks and helmets. The bikeshare was also a result of a coordinated internal effort at Anythink, as staff integrated the bicycles into the collection system; solicited and evaluated contractor bids for supporting infrastructure improvements; coordinated maintenance with a local bike shop; and engaged in marketing initiatives.

An interview with Minnesota DOT highlighted micromobility models outside of the Twin Cities. The bikeshare in Rochester, MN launched in 2016 and has a fleet of 200 bikes. The system is currently free to use thanks to a collaborative network that includes multiple City departments, the Mayo Clinic, the Rochester Public Library, and other non-profits that maintain the bikes (City of Rochester 2020). Residents and visitors can check out bikes at the public library on a daily or weekly basis. The fleet includes two electric-assist cargo bikes. Willmar, MN started its own program, BikeWillmar, in 2019 using general funds and support from local businesses (City of Willmar 2021). The bikeshare system has 40 bikes and 11 docking stations and operates from spring through the early fall. Users can check out bikes using the vendor’s mobile app (Koloni). Other smaller systems have popped up throughout the state but have not had staying power. Often, shared mobility in rural environments is collocated with recreational opportunities such as trails. First mile and last mile connections to transit are less important in these rural settings since transit in this context is primarily door-to-door and on-demand.

4.2.2 Business Model Decision Matrix

Table 4 provides an overview of common ownership and operating models for micromobility based on a literature review and interviews. The table includes the strengths and weaknesses for each type of model as well as considerations and specific examples that jurisdictions can refer to while conceptualizing a potential micromobility program. Transit and Micromobility (TCRP Research Report 230) includes a toolkit to inform decisions about partnering.

| Types of Models | Strengths | Weaknesses | Considerations | Examples

|

| Non-profit owned and operated |

|

|

|

|

| Privately owned and operated |

|

|

|

|

| Publicly owned, 3rd-party operated |

|

|

|

|

| Publicly owned and operated |

|

|

|

|

| Transit agency owned and operated |

|

|

|

|

Some considerations in determining the appropriate model include:

- What is the source of start-up funds?

- What is the source of on-going capital and operating costs? (Note: FTA funds will not cover all aspects of a bikeshare or micromobility system)

- Who will own the micromobility equipment (including vehicles and stations)?

- Where will micromobility vehicles be stored?

- Will the system include e-bikes or e-scooters? If so, is there capacity to address charging needs and necessary supportive infrastructure?

- Who will be responsible for operating and managing the system?

- What role will public, private, and non-profit entities have in the micromobility system?

- What is the appropriate fleet size for the system?

- To what extent will the system need to make a profit?

- How long will permits be issued to vendors? (Year-to-year permitting can lead to vendor turnover)

- Will the system operate year-round, or only during specific seasons?

4.3 Program Governance

Program governance models can help provide a framework for decision making, roles, and responsibilities when multiple stakeholders are involved in micromobility programs. A micromobility program may have multiple stakeholders that help run and maintain the service, but the service may appear as a singular entity to the public. Good governance and oversight can protect the brand and instill trust in the micromobility services that programs provide.

Partnerships and collaboration are critical to a micromobility program’s success. Anythink Library in Commerce City, Colorado received 30 donated bikes and went to work on preparing a business plan. The plan incorporated library departments that would be involved with the bikeshare and identified where external assistance was required, such as with the City for permitting and a local bike shop for maintenance. Anythink was the lead decision maker but relied on City and vendor support to establish the program. In Meadville, Pennsylvania, CATA formed a non-profit to apply to grants and funding for which municipal agencies are not eligible. The subsequent bikeshare system is operated directly by CATA and funded by the non-profit organization they control.

Jurisdictions have the power to stipulate the conditions to which vendors must adhere and provide oversight. One interviewee encouraged jurisdictions to be active partners in any new micromobility program. Micromobility is an innovative product that requires time and opportunity to take off. The interviewee emphasized that jurisdictions should be very involved to make sure that new systems have the resources they need and that they serve community needs.

CARTA provides an example of the potential role that transit agencies could play in implementing micromobility systems, and how that role may change over time. CARTA funded an initial bicycle fleet project in 2007 and later sponsored a permanent bikeshare program (now known as Bike Chattanooga) as an FTA project. In the early planning phases for Bike Chattanooga, stakeholders needed to decide their roles and responsibilities and whether the bikeshare should be run by a non-profit, private, or government entity. CARTA emerged as the fiscal manager, initially owning the bikeshare assets and managing fiscal and funding matters with the original goal of the bikeshare being a managed entity within CARTA. However, early labor and insurance concerns led CARTA to pursue an external vendor to operate the system. The bikeshare’s assets were later transitioned to city ownership. In 2013, the city took over direct operation of the bikeshare. Today, CARTA assist with joint grant applications but is no longer directly involved in program management.

4.4 Regulations

4.4.1 Regulatory Approaches

Local jurisdictions are frequently the body that regulates micromobility, and vendors, partners, and transit agencies are the ones that must follow these regulations (TCRP 2021). Jurisdictions regulate new and existing development and the usage of public space, including right of way, and set public policy. They may determine the application process for micromobility vendors, operating fees and terms, the conditions to which vendors must adhere, and the costs vendors may incur (ROW provision, signage, etc.) to establish operations. A jurisdiction’s individual choices are important at a larger level if there is potential to build a regional system (requiring all participating jurisdictions to use the same vendor). Partnerships and coordination between jurisdictions during the vendor selection process may provide opportunities for more favorable pricing or cost sharing.

Some common elements of micromobility regulations include establishing areas where micromobility is permitted to operate; determining fleet sizes and parking requirements; safety for riders and the general population; vendor reporting, data, and insurance requirements (TCRP 2021) as shown in Table 5. Compliance with these regulations determines whether a micromobility program will be allowed to operate and continue operations. The Shared Use Mobility Center (SUMC) maintains a searchable, international Micromobility Policy Atlas of shared bike, e-bike, and scooter policies.

| Regulatory Area | Example |

| Operating service area | Scooters are geofenced to stop working outside a specific zone. Can be used to restrict access to an area, like a park or pedestrian street. |

| Fleet sizes | 50 scooters are permitted for use in a pilot project. |

| Parking | Scooters may not be left on the sidewalk at the end of a trip or vehicles required to be parked at designated areas in the public right-of-way. |

| Safety | Operator must develop a communication plan for safety outreach. |

| Reporting | Operator must provide an annual summary report. |

| Data sharing and standards | Operator must provide monthly reports that include number of rides taken, number of rides per vehicle per day, anonymized trip data, etc. More information on data standards is in 4.5.1. |

| Insurance | Operator must meet insurance requirements to operate in the jurisdiction. Vendor indemnifies jurisdiction of any responsibility / liability related to program operations. |

| Vehicle Distribution | Operator must ensure a minimum number of vehicles are available each day in every ward of the city. |

Jurisdictions may also consider their overall attitude and approach towards supporting and regulating micromobility. The American Planning Association’s Planning for Shared Mobility (2019) lays out three frameworks to describe the extent to which jurisdictions can view and support shared mobility: either as an environmental benefit with maximum governmental support; a sustainable business with moderate governmental support; or as a business with minimal governmental support. Deloitte Insights summarizes possible approaches to regulating micromobility on a sliding scale of regulation (Zarif, Pankratz and Kelman 2019). These approaches include jurisdictions entering into a public-private partnership with a vendor; a more open approach with limited regulations, in particular for new markets; express bans with potential impoundments; or a formal, permitting process for which vendors must adhere to a jurisdiction’s set of rules (Figure 16). Deloitte suggests regulation that adapts as a market evolves; micromobility sandboxes that allow for regulatory testing; outcome-based regulation; and risk-weighted regulation (2019) More information on establishing regulatory policies and permitting guidelines is in the Regulations and Permitting Worksheet.

4.5 Technology and Organizational Requirements

Transit agencies need varying skills to deploy or monitor a micromobility program, depending on the program’s structure and the agency’s anticipated level of involvement. This section provides an overview of the skills, systems, and expertise that transit agencies will need as they implement programs and monitor vendors that operate programs. Anticipated requirements are broken into technology-related expertise and organizational capacity.

4.5.1 Technology-Related Expertise

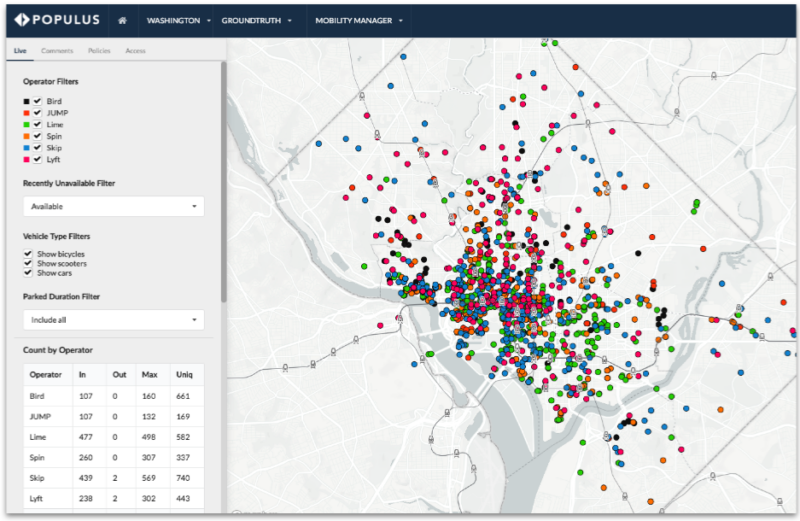

From a technological perspective, transit agencies would need to be familiar with industry data standards. This starts with the General Bikeshare Feed Specification (GBFS) (NABSA 2021). GBFS, similar to the General Transit Feed Specification (GTFS), dictates a standardized format for micromobility data that ensures integration with a wide variety of apps and mapping services. GBFS is how systems provide real-time information about micromobility which can be collected, analyzed, integrated into applications, and facilitate trip-planning. The Mobility Data Specification (MDS) is another data standard but differs from GBFS in that it is primarily for communication between municipalities and micromobility providers. Whereas GBFS is only for bikeshare, MDS data can be gathered for any micromobility or MaaS solution. GBFS data is captured in real-time, but MDS data includes historic information like vehicle location over time, which includes sensitive data about user locations and is therefore not for public-facing uses. Common data, as well as data that is not included in MDS, is listed in Table 7. This table does not list all MDS data, but more information can be found here.

| Included in MDS | Not Included in MDS |

| Vehicle Location | User Names |

| Vehicle Status | Payment Information |

| Vehicle Trip Duration/Distance | Unique Rider ID Number |

| Vehicle or Device ID | User Contact Information |

| Vehicle Trip Origin/Destination | Trip History of Each User |

| Vehicle Trip route | Demographic User Data |

Aside from data, agencies may consider integrating micromobility services into their fare payment systems. Integrating multiple modes of travel onto a single payment method provides a seamless experience for micromobility users and transit riders. CARTA led a pilot program with the goal of integrating Chattanooga’s bikeshare, CARTA services, and car share onto a single stored value card which could be used as a bikeshare key fob and a card that could be tapped to ride CARTA. Apps such as Transit already have partnerships with micromobility services that allow users to pay for micromobility rides directly in the app. Integrating payment for micromobility may be easier if transit agencies are already using apps for trip planning and fare sales.

4.5.2 Organizational Capacity

To implement a program, transit agencies would need staffing capacity across several departments. These include procurement and legal to navigate the vendor selection process, and human resources and managers to determine whether the agency has in-house expertise and capacity to fulfill its defined role in the system. Depending on the structure of the program, the agency may need to identify resources to maintain the system (including fleet and any electric charging stations), balance bikes or other vehicles, and monitor vendor performance. Some off the shelf solutions can help agencies or jurisdictions monitor micromobility vendors. Some examples include software to monitor how micromobility vehicles are ridden and parked; operations and fleet monitoring; and street, curb, and new mobility fleet management.

Agencies may also need to coordinate with local jurisdictions for any necessary permitting and regulations (e.g., data sharing, ROW, infrastructure, etc.). Small communities may need to be more active in micromobility programs than their larger counterparts, as vendors may only be willing to provide the vehicles while the transit agency or jurisdiction operates the program.

4.5.3 Risk Management

Three groups of risk and liability facing transit agencies are in Table 8. The table is not meant to be one-size-fits all given each agency’s unique situation. Some topics included in the table are explained in greater detail below.

| Legal and Financial Risks & Liability | Customer Risks | Institutional Risks |

| Insurance | Accessibility | Vendors are in a volatile industry; operations may cease without warning |

| Legal Requirements | Vendors subject to jurisdictional regulation | |

| Data Privacy and Security | Privacy Concerns | Agency staffing shortages |

| Future Title VI Requirements | Dissatisfaction with Brand | Labor unions buy-in |

| Ease of use (e.g. payment, integration with other agency services) | Reputational risks | |

| Facility space | ||

| Cost and funding impacts |

Legal and Financial Risks and Liability

When CARTA planned on operating bikeshare in Chattanooga, the agency ran into two roadblocks, one of which was insurance. The agency was in a public municipal pool and insurance providers had concerns about risks associated with micromobility (limited bike safety metrics were available at the time). CARTA addressed this problem by contracting with a vendor that could obtain insurance and operate the system. Transit agencies interested in in-house operations will need to consider how to secure insurance. Information on federal civil rights requirements is available here: https://www.transit.dot.gov/regulations-and-guidance/civil-rights-ada/civil-rightsada.

Data Privacy

Agencies will need to determine how to keep user data private and secure and understand the importance of being trusted stewards of personal information. For example, routine trips can become so-called personally identifiable information (PII) that can identify an individual when combined with other data sets (NACTO 2019). The Open Mobility Foundation, which developed MDS, published a privacy guide for cities.

Customer Risks

Customers may have accessibility concerns, ranging from the availability of accessible vehicles (such as adaptive bikes); the ability to pay without using a smartphone or credit card; and the even placement of vehicles throughout a transit agency’s service area. Dissatisfaction with a micromobility system that the transit agency operates or is otherwise affiliated with may lead to dissatisfaction with the overall brand.

Institutional Risks

Agencies that partner with micromobility vendors should consider the industry’s volatility, which means that operations could be impacted at any time. These vendors are also subject to jurisdictional regulation. From an agency perspective, agencies should consider whether they have adequate staffing and facilities to accommodate micromobility systems and the impact, if any, on micromobility systems on agency funding. Agencies may also face reputational risks if micromobility programs do not run smoothly.