New Fare Payment Systems and Payment Technology Fare Background: Systems, Payments, and Policies

- Date: November 8, 2022

Jump to section

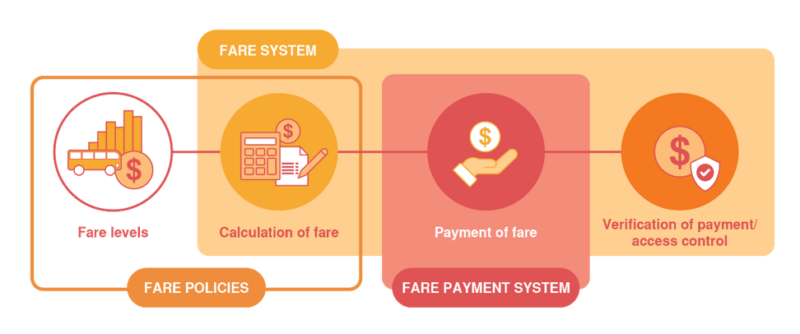

Deployment of a non-cash, technology-based fare system requires understanding the three key fare components: system, payments, and policies. The fare system is the ecosystem to calculate, verify, and collect the payment of fares. Fare systems can be procured through vendors who provide services and features to meet the fare needs of transit agencies and provide the technology platform. Fare payments are the mechanisms to pay the fare. The fare payment mechanisms discussed in this guidebook include contactless bank cards – Europay, Mastercard, and Visa (EMV) secure payment technology, smart cards, and mobile ticketing. Identifying the features that work best for a transit agency requires understanding the available technologies and the integration capabilities with the agency’s fare structure and policies. The fare structure is the system set up to calculate how much to charge a passenger at any given time.

Fare Systems

Most commonly, transit agencies utilize physical fareboxes located onboard vehicles which collect cash fares. Cash fares are then reconciled manually by the agency for the purpose of revenue calculation and reporting. Now, transit agencies have more options than ever before for new technology-powered fare systems that calculate, verify, and collect fares. Fare systems can be verified either visually or with a physical validator to accept a non-cash, technology-based fare.

To take advantage of technology-driven fare systems, transit agencies can contract with vendors such as fare systems providers, financial institutions, or credit card companies to provide the fare system or payments that allows riders to utilize fares other than cash. To procure a fare system, typically, a transit agency must develop a Request for Proposal (RFP) document with requirements, specifications, and/or features they want to be included in the fare system, then the agency must issue RFP through a formal bidding process to procure services via a vendor. Upon identifying qualified vendors and procurement of services, the agency must install validators, if applicable, train and educate staff and operators, market services to the public, and initiate deployment. See the Best Practices and Recommendations section for more information on deploying a technology-based fare system.

Open-loop vs. Closed-loop Systems

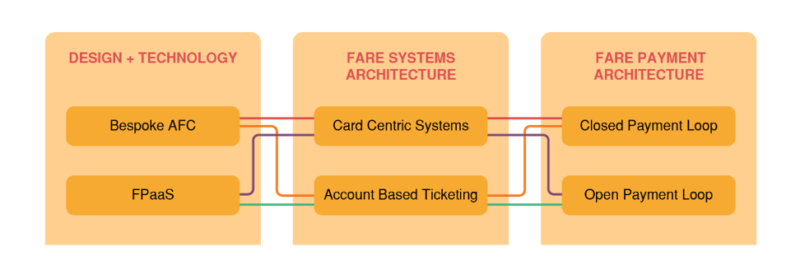

Open-loop systems leverage existing open ‘tokens’ or unique identifiers typically associated with a smart card, student ID, or contactless bank card. ‘Tokens’ are randomly generated unique IDs assigned to EMV cards/devices that replace the account number (the 8-19 digit number that appears on a card), providing enhanced data security. Open ‘tokens’ are not proprietary to the transportation system but are part of the payment chain industry. This allows for flexibility in fare media because riders can use existing ‘tokens’ provided by an entity like a bank or university. Smartphones, wearables, and contactless credit cards are the most common devices suited to function in an open system; these devices allow for communication with fare system equipment via NFC or Bluetooth. Open-loop systems come with micropayments (small transaction amounts ranging from less than one cent to several dollars) because the processing fees associated with the card-based transaction, which the agency must pay, are high. To alleviate some of the cost, systems can implement fare aggregation where they aggregate transactions daily, so there are fewer small transactions. Open-loop systems are typically paired with an account-based back office system to calculate fares and authenticate that riders have the appropriate funds for their journey, in turn reducing the cost associated with issuing and managing fares for the transit agency.

Closed-loop systems are more traditional for fare payment systems, where only fare media issued by the transit agency can be used for fare payment. Smart cards issued by the transit agency or magnetic stripe tickets encoded with transit agency data are common ‘tokens’ used in closed-loop systems. Unlike open-loop systems, these types of fare media cannot be used by riders to pay for other goods or services outside the transit agency and are exclusive to transit. Closed-loop systems work offline and rely on stored-value, card-centric systems to process fares. All front-end equipment in a card-centric system must be able to update travel records and/or perform fare calculations directly to the card each time it is presented, including checking that the card is authentic, the right values are present, and the data on the card is updated at the time of transaction.

| Considerations | Open-Loop System | Closed-Loop System |

| Key Features |

|

|

| Capital Considerations |

|

|

| Operating Considerations |

|

|

| Complexity |

|

|

| Hardware Requirements |

|

|

| Typical User |

|

|

| Considerations for Maximizing Usage |

|

|

Fare Payment as a Service (FPaaS) vs. Bespoke Automated Fare Collection (AFC)

Many transit agencies may have a traditional bespoke, automated fare collection (AFC) system, which was developed specifically for their usage. Bespoke AFC systems are an end-to-end solution for collecting fare payments by digitalizing the issuance of tickets; however, they rely on farebox infrastructure using software and hardware designed with specific specifications. Bespoke systems can be expensive to build, maintain, and update and tend to be closed in nature with the inability to integrate with new systems.

Compared to bespoke AFC systems, transit agencies may look to utilize cloud-based subscription systems such as Fare Payments as a Service (FPaaS) systems. Subscription-based models are often referred to as Software as a Service (or SaaS) because every system utilizes the same platform and can vary by software complexity from straightforward to complex. Straightforward software includes a base level of software required to accept fare payment. Comparatively, a more complex SaaS may include a more detailed software whose features allow for open integrations to link to other platforms, mobility as a service (MaaS), and digitalization of fare payments. Vendors can also provide hybrid SaaS offerings by providing a cloud-based service that allows for some level of integration with other platforms but is straightforward to select and purchase passes.

FPaaS allows agencies to procure a fare payment platform at a much lower cost of entry because the vendor charges a monthly fee (or takes a percentage of fare revenue collected) instead of charging initial high upfront capital costs. By utilizing FPaaS, transit agencies can implement the latest and greatest fare technologies with automatic firmware/software updates that the vendor can deploy to the transit agency as updates are available. By using the SaaS platform as a baseline, each transit agency can use the same FPaaS platform that is then configured specifically to that agency’s needs. FPaaS also utilizes open-loop infrastructure, allowing systems to seamlessly integrate with other technology.

| Fare Payments as a Service | Bespoke Automated Fare Collection | |

| Key Features |

|

|

| Capital Considerations |

|

|

| Operating Considerations |

|

|

| Complexity |

|

|

| Hardware Requirements |

|

|

| Typical User |

|

|

| Considerations for Maximizing Usage |

|

|

Fare Payments

Transit agencies have multiple fare payment options to choose from, ranging from traditional methods to modern, technology-driven solutions. In the past, riders typically paid fares with cash, exact change, paper passes, or physical tickets issued by bus drivers, ticket vending machines, or fare boxes. Today, agencies can adopt digital fare payment systems that provide greater convenience, flexibility, and accessibility for riders.

This section describes three fare payment types: contactless cards enabled with EMV technology, smart cards, and mobile ticketing. Fare payments are a crucial component of a fare payment ecosystem, including the technology needed to process fare payment types. Transit agencies should consider the associated capital and operating costs, hardware requirements, and level of complexity to integrate the fare payment. Additional consideration should be given to the utilization of the fare payment and removing barriers for riders.

Contactless Cards (EMV)

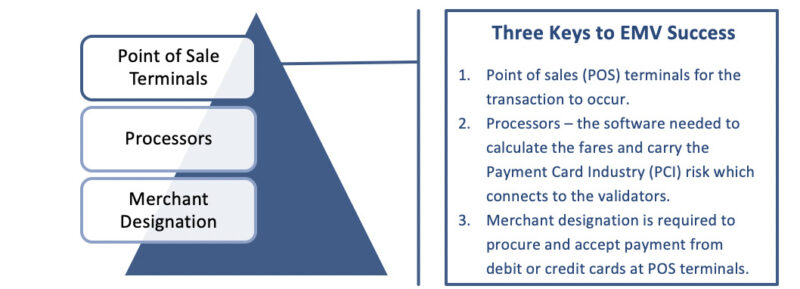

Contactless enabled bank cards, or EMV, are a global standard for cards equipped with computer chips and the technology used to authenticate chip-card transactions. EMV technology can enhance security between merchants and customers by securing banking data. As of 2023, 66% of debit and credit cards issued in the U.S. have EMV technology. The EMV technology allows users to tap-and-go with their card to access open-payment systems. For transit, passengers can use their bank-issued contactless credit or debit card to tap a payment reader to validate the fare and access transit services.

The first time a card/device is tapped within the transit system, the reader sends a request to authorize the transaction to the merchant (transit agency), which forwards it to a financial institution (the bank that issued the card). The financial institution performs a series of checks and either authorizes or denies the transaction. This is all done offline so as not to slow down the boarding process. If the financial institution denies the card, this information is sent back to the payment processor (software on the validators), and the card is put on the ‘bad’ list. It will be immediately rejected upon the next tap on the validator. For the initial transaction with an EMV card, first ride risk occurs, in which the payment authorization could be declined following the initial tap transaction, which could mean no fare is collected. The financial institution often carries the first ride risk, but a transit agency may also be accountable if not detailed in vendor contracts. Financial institutions also carry the Payment Card Industry (PCI) Data Security Standard (DSS) or set of requirements intended to ensure that all companies that process, store, or transmit credit card information maintain secure information.

Debit and credit cards enabled with EMV technology can be stored in a digital wallet on a smartphone, computer, wearable, or tablet. The data can be transmitted to other devices using wireless technologies (NFC or Bluetooth) to make payments. Popular mobile wallets include Apple Pay, Google Pay, and Samsung Pay. The payment card data is scanned or manually entered into the application and sent for validation to the payment network. At the end of this process, the user can make payments on the accepted terminals using their mobile device instead of a physical debit or credit card. The payment card data is never shared with a merchant when making payments or stored on the device; instead, a security feature called tokenization is used. Tokenization is the process of replacing confidential data with non-confidential data called a ‘token.’ Mobile payment applications, including popular mobile payment services such as Venmo and Cash App, utilize payment ‘tokens’ to secure data and allow users to access open payment systems.

| Considerations for Contactless Cards (EMV) | |

| Capital Costs | EMV cards are issued to users via banking institutions; therefore, transit agencies have no capital costs to purchase the cards and issue them to users. Transit agencies need to purchase hardware such as card readers that are EMV compliant and process and approve transactions. Typical costs for EMV hardware ranges from $900 (if the validator only reads EMV payments and up) to $1,500 if it also can validate several fare media types. |

| Operating Costs | Transit operators must pay acquiring banks’ merchant service fees (i.e., Visa, Mastercard) with a range between 1.5% to 4% of the total transaction plus a per-transaction amount that could range from $0.0 to $0.49. Fees vary based on the card type, the type of transaction, financial institution, the card processor, and the value of the transaction.

Agencies can select financial institutions to provide the service directly or work with other technology vendors. Depending on the vendor selected, additional fees may incur, ranging between $2,000 to $3,000 a month. These fees may or may not include the abovementioned fees and will vary based on the contract. |

| Hardware Requirements | Transit agencies will need to procure a validator that is EMV compliant. Due to changing banking standards, the hardware on EMV validators may go obsolete quicker. |

| Complexity | High operational complexity. Contactless cards require compliant validators and additional considerations for fraud risk, compliance with payment industry standards, compatibility with fare capping, and integration with the back-end system. Complexity tradeoffs may be worthwhile for high ridership transit systems. |

| Typical User | A single rider using their bank-issued, EMV technology equipped debit or credit card to access transit services. |

| Considerations for Maximizing Usage | This fare payment type may have a disparate or disproportionate impact on unbanked populations without access to an EMV card, including youth riders. These populations will require an additional fare method to ride transit.

The tokenization element of contactless cards makes it challenging for fare capping with contactless cards. Fare capping integration with EMV cards can be complex and may require riders using the same card, tapping on and off the vehicle, and back-end configurations. While fare capping is feasible with contactless cards, the setup and management is challenging. |

Smart Cards

Smart cards are cards approximately the same size as credit or debit cards that are typically issued by transit operators to be used within their private ticketing system. There are three models for Smart cards: contactless, magnetic stripe, and virtual. Contactless smart cards function similarly to contactless EMV cards. They are enabled with a microchip or radio frequency identification (RFID) technology that allows users to tap the card on a reader. Smart card systems can be either account-based or card-centric, but in both cases, the transit system has its own fare media and accounting network for the card. Users must load funds onto the card, and it can only be used for that network. A debit/credit card can be linked to a smart card, and funds are automatically withdrawn from the account with each transaction.

Smart cards can work with card-centric systems or with ABT by acting as an identifier to log a passenger’s access to the transit system. For card-centric systems, smart cards interact offline, without internet or cellular connectivity, with onboard vehicle devices. For ABT, smart cards act as ‘tokens’ working in tandem with a back-office via an internet or cellular connection. Contact smart cards have magnetic stripes the user must swipe through a reader. Special smart card readers are required onboard each vehicle and are typically part of a larger electronic farebox system to process fares for both card types. Virtual smart cards can be emulated on mobile devices if the agency elects to have this feature and are typically used for ABT.

Transit agencies may elect to utilize a retail partnership network to offer accessible solutions for transit riders to load value onto their smart card. For example, InComm Payments provides prepaid products, services, and transaction technologies for retailers, brands, and consumers. Transit users who may be unbanked or do not use a financial institution can load cash onto compatible smart cards through local InComm Payment retailers, such as gas stations, grocery stores, or other locations where gift cards are typically sold. The smart cards, now loaded with a stored value, can be used to access transit services.

| Considerations for Smart Cards | |

| Capital Costs | A per card cost is often passed onto riders and can range anywhere from $2 to $5 per card. Stand-alone validators range from $1,200 to $5,000 each, depending on the type selected. |

| Operating Costs | Retail partners often charge transaction fees between two and five percent, which is taken from the total fare revenue collected before being transferred to the transit agency. |

| Complexity | Medium complexity depending on the type of smart card, either physical or virtual, and the number of retail partners. |

| Hardware Requirements | Transit agencies needed, at a minimum, a computer with a web browser to manage smart card accounts and offer customer support. Agencies can choose the validator type with barcode scanners, near-field communication (NFC), or Bluetooth capabilities. |

| Typical User | Single full fare or reduced fare eligible rider, with or without a smartphone or bank account, who utilizes the smart card issued by the transit agency to access transit services. |

| Considerations for Maximizing Usage | Available to riders regardless of whether the rider has access to a bank account or smartphone; however, some agencies may elect to require a minimum dollar amount to be loaded onto the smart card. |

Mobile Ticketing

Mobile ticketing is the process in which passengers can select a fare type, pay for the fare, and display the mobile ticket onboard vehicles using their mobile phone. Mobile ticketing is the key feature of mobility apps designed to increase rider convenience replacing the face-to-face interactions previously required to purchase fares. Mobile tickets are a form of ABT in which a rider needs to have an account, often tied to a phone number or email address, to purchase fares. The types of mobile tickets offered should mirror existing transit agency fare structures, including the fare type (e.g., single-ride tickets or monthly passes). Riders can purchase fares by linking a debit/credit card or by adding cash to their account at approved retail locations, similar to how a rider may load a smart card. Upon boarding the bus, riders activate the mobile ticket and either validate the ticket by showing the bus operator or scanning it on a validator.

The mobile ticketing applications can be configured to offer reduced fares and confirm eligibility. Examples of reduced fares include senior fares, disabled fares, and fares for institutional partners such as employers or universities. Mobile ticketing can accommodate requirements by transit agencies to verify eligibility for reduced fares in two ways. First, mobile ticketing apps may prompt passengers who are purchasing reduced fares that they will be required to show proper proof of identification, as aligned with the existing agency fare policy, to the driver upon boarding. Second, some mobile ticketing apps allow eligibility to be verified through the device. For example, mobile ticketing apps can be configured to allow an authorized agency, in addition to the transit agency, such as the Department of Motor Vehicles or Department of Veterans Affairs, to verify eligibility status, including age, disability, or veteran designation. Employers and educational institutions can work with transit agencies to be set up as third-party authorized users to manage users and link accounts to reduced fare types. For example, a local university student can link their mobile devices to their school email address, designated and approved by the university, as a third-party authorized user. As a result, when the student activates the mobile ticket via their email address linked account, it is already pre-designated as a reduced fare.

| Considerations for Mobile Ticketing | |

| Capital Costs | Capital costs are associated with procuring mobile applications that support mobile ticketing. Costs range from $0 to $150,000 depending on the mobile application; cost includes onboarding, set up, and site visit.

Validator options include:

Bus Technology (i.e., modem or antenna): $500 – $600 each. |

| Operating Costs | Operating costs for mobile ticketing can be a tiered fee structure which uses a percent share of the fare revenue collected from the application or a flat, fixed per month fee:

If retail partnerships are established, additional transaction fees may be incurred by the transit agency, which can range from less than 10 cents per transaction to 8 percent of the total transaction, depending on the retail network and payment methods accepted. |

| Complexity | Low to High – varying complexity depending on the vendor selected, choice between visual validation and readers, agency fare structure, number of vehicles, and equipment required. |

| Hardware Requirements | Mobile ticketing can be verified visually by the bus operator or with scanners/validators. Depending on the technology, vehicles may need to be outfitted with power, modems, cellular connection, and/or pedestal. |

| Typical User | Single full fare or reduced fare eligible rider with a smartphone who utilizes the transit agency’s dedicated mobile ticketing platform to access transit services. |

| Considerations for Maximizing Usage |

|

Other Considerations

Validators

Fare system validators can utilize different technologies to accept fare payments. For example, Near Field Communication (NFC) and Bluetooth are wireless technologies that enable short-range communication between compatible devices, such as smart cards, contactless credit cards, or mobile wallets. Other validators may use proximity validation or barcode scanning, a technology typically seen in grocery stores at self-checkouts, allowing a user to display a barcode or QR code that is scanned and verified. When using mobile payment, agencies can either elect to use physical validators onboard vehicles to verify payment or elect not to install physical validators onboard vehicles and use visual validation in which an operator “visually” inspects the fare is activated appropriately.

Features

Features of fare systems vary by vendor and can include, but are not limited to, the following:

Trip Planning

Fare system vendors are distinct from trip-planning providers, who offer mobile apps for viewing routes, schedules, and real-time arrivals. However, some fare systems integrate with existing trip-planning apps, such as Google Maps.

Transit Rewards

Some fare systems allow agencies to offer rewards to riders, similar to loyalty programs at retail stores. Agencies can configure these systems to provide percentage discounts, free trips, or promotional coupons for local businesses.

Retail Partnerships

Some vendors partner with national retailers to let riders load funds onto a mobile app or smart card by paying cash at a store’s register, typically through networks like InComm Payments. Others work with transit agencies to establish new partnerships with local retailers.

Purchasing Multiple Passes

Fare systems can be configured to allow riders to buy multiple passes or trips at once or restrict them to one pass per device at a time, depending on the agency’s fare policies and technology.

Pass Activation

Fare systems can activate passes based on a set time period—such as 31 days, seven days, three days, or one day—rather than being tied to a calendar month, giving riders more flexibility in purchasing and using their passes.

Reduced Fares

Transit agencies can offer reduced fares for eligible groups, such as seniors, people with disabilities, and students. Some fare systems allow riders to select and purchase reduced fares digitally, though additional in-person verification may be required onboard.

Smart Card Integration

Some fare systems support smart card integration, either for agencies that already use smart cards or those looking to introduce them.

Third-Party Authorizations

Fare payment systems can allow third parties—such as schools, universities, employers offering transit benefits, and human services organizations—to manage fares and user accounts on behalf of riders.

Data Reporting and Reconciliation

Fare systems can automate data collection and generate reports that help transit agencies meet National Transit Database (NTD) and other reporting requirements.

Open Fare Data

While not a fare payment method itself, the General Transit Feed Specification (GTFS) plays an important role in how riders access fare information. GTFS is an open data standard that allows transit agencies to publish service information—including routes, schedules, and increasingly, fare details—in a structured format that can be read by apps and digital platforms.

In recent years, updates to the GTFS-Fares specification have made it possible to share more complex fare structures, including zone-based pricing, fare capping, and eligibility-based discounts. Although still a relatively recent development, GTFS-Fares enables agencies to make their fare information more transparent and accessible to the public.

By publishing fare data in GTFS format, agencies can ensure their fare policies appear in widely used trip-planning apps such as Transit App and Apple Maps. This integration improves the rider experience by helping travelers understand the full cost of a trip upfront—alongside real-time arrival and routing information—and supports a seamless transition between planning and payment.