Digital Tools to Facilitate Complete Trip Planning Providing a Digital Tool for Complete Trip Planning

- Date: February 3, 2023

Jump to section

Aims and Shortcomings

Overall aim of the Complete Trip concept

When individuals can navigate a transit and mobility system largely without worry, a more “seamless” Complete Trip is in place. They can move around in their physical surroundings and leverage digital tools effortlessly; they know they have been considered as improvements were made.

To get to this place, all the components of the Complete Trip—the travel modes and collaboration as well as physical, service, governance, and technology infrastructure—must work together in such a way as to reduce uncertainty for people. This means people don’t ask themselves as often – Are these two modes going to connect well? Will my wheelchair fit there? Is this bike lane going to continue? – because they know the answers. They have personal experience finding this out for themselves, or the answers are available online from a trusted source. When physical and psychological strain is kept to a minimum during the customer experience, trust and confidence in the transit and mobility system can flourish.

Shortcomings of digital trip planners

The general purpose of a digital trip planner is to enable users to compare mobility options and select the itinerary that best meets their personal requirements. Although trip planners have been around for more than a decade, they still have major shortcomings that must be taken into account. As explained in Section 2.1.1 of the Guidebook, trip planning is a process that may or may not involve digital tools. The process of trip planning involves evaluating different options, anticipating the experience of taking these options, and selecting an option.

First, multimodal trip planners (i.e., those that enable searching for options across two or more modes) and intermodal trip planners (i.e., those that enable individual trips with two or more modes to be shown) still do not include all the transit modes that are commonly used. Widely used, commercially available trip planners such as Google Maps, Moovit, and Transit do not include a default option to display demand-response transit (DRT) and on-demand transit modes. In many places, such as low density and rural areas, DRT is the only local transit option. Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA) paratransit and human-services transportation (HST) are types of DRT that add on the additional requirement of eligibility. Typically, these DRT services are available to people in certain age groups, with certain types of disabilities, with certain medical conditions, and/or going to specific destinations often connected with their age/disability/medical condition. On-demand transit, as explained in Section 2.2.3, is becoming increasingly popular in all kinds of geographic contexts. In some cases, on-demand transit is replacing an existing DRT service, essentially using more modern technology to operate a long-standing service.

The “intermodal trip planner” project in Northwest Oregon is an exception to the rule. The Oregon trip planner is based on the Open Trip Planner (OTP) open source software, which includes demand-response as well as many other trip options, explained further in Section 2.2.2.

Second, digital trip planners and related tools rarely include all of the critical decision-making criteria needed to make thoroughly informed mobility decisions—such as safety and comfort. This could include key details about individual bus stops, sidewalk conditions, and other safety-related information and could be provided for individuals with disabilities in mind or from a more general perspective. Projects such as the “bus stop accessibility map” in Northwest Indiana are rare, and projects that detail sidewalk information as shown in Section 2.3 in the project table, notably the “AccessMap” project in Seattle, WA and the “Accessibility Mapping Project” for the University of Pennsylvania, are uncommon as well.

Third, trip planning is connected with other customer experience processes such as trip booking, payment, and navigation, but apps do not always connect these functions seamlessly. Major inroads have been made to better integrate these functions into common interfaces but, currently, it is still typical for the customer to bounce around multiple apps for different steps in the process—even to different apps for different transit providers in the same geographic area.

In short, for all the progress that has been made with trip planners over the past decade, glaring omissions remain. Before digital tools were available, people performed trip planning calculations mentally. Now that digital tools have entered the picture, some aspects of the mental calculations are aided significantly with trip planning tools—but not all. Simply because digital tools exist does not mean the technology aspects of trip planning are all addressed adequately.

Guidelines for Improving the Complete Trip Through Digital Tools

For professionals to assess if their digital tool and trip planning effort supports the aims of the Complete Trip, a set of guidelines are provided that break down specific Complete Trip aims and pinpoint the corresponding role that the digital tool should have.

#1: Complete information

Complete Trip Aim: The Complete Trip requires complete information for all people in order to reduce uncertainty.

Digital Tool Role: Provide digital tools that display the most complete information possible, even if that means providing multiple tools—including the full range of modes and all the information on personal requirements that users may need.

#2: Accessibility

Complete Trip Aim: The Complete Trip requires accessibility for all.

Digital Tool Role: Provide digital tools that all users can access. Refer to standards such as the Web Content Accessibility Guidelines (WCAG) and consider having a specialist review the tool; this could come in the form of assistance from a local university, a consultant, or a professional contact.

#3: Intermodal options

Complete Trip Aim: The Complete Trip requires all options to be included—both single-mode and intermodal options—making them as seamless as possible.

Digital Tool Role: Provide digital tools that give special attention to intermodal options; introducing a transfer between modes requires additional attention. Make sure that the complete intermodal trip is as seamless as possible for the end-to-end journey.

#4: Connected plan, book, pay, and navigation steps

Complete Trip Aim: The Complete Trip requires seamlessness throughout the end-to-end journey.

Digital Tool Role: Provide digital tools that assist with the typical steps that individuals take physically and digitally. They plan for the trip, may need to book it depending on the mode, pay for the trip, and navigate various trip segments. While trip planning tools may be the initial focus, it is also important to consider how book, pay, and other steps individuals will take will be addressed—perhaps in future projects and connected in some way to the trip planner.

#5: Ability to update status of services and physical infrastructure

Complete Trip Aim: The Complete Trip requires that physical infrastructure and service infrastructure are considered as key components.

Digital Tool Role: Provide digital tools that ensure that the status of physical and service infrastructure is reflected within the tool, while allowing for that status to change temporarily (such as with an elevator outage) or permanently (such as with a sidewalk upgrading project).

#6: Foundation for collaboration and governance

Complete Trip Aim: The Complete Trip requires that collaboration and governance infrastructure are considered as key components.

Digital Tool Role: Provide digital tools along with a longer-term strategy that considers the collaboration and governance setup needs to ensure success over time.

#7: Holistic approach to digital and mental calculations

Complete Trip Aim: The Complete Trip requires technology infrastructure and digital tools to be considered holistically along with other needs users have—including those needs currently underserved by data and digital tools.

Digital Tool Role: Provide digital tools that make the most of current digital capabilities while considering the necessary mental calculations that will occur in tandem through design of the complete user experience. Allow for the fact that current trip planners do not yet enable the trip planning calculation to be done 100% digitally.

#8: Customer experience focus

Complete Trip Aim: The Complete Trip is customer-centric, keeping the customer experience at the center of the effort.

Digital Tool Role: Provide digital tools that have had thorough input from customers, early on to help determine the best path forward and later to assess the usability and functionality of the tool.

How to Approach Providing a Digital Tool for the Complete Trip

This section of the Guidebook offers guidance on how professionals can take their next steps toward providing a digital tool for complete trip planning. One highly applicable resource is N-CATT’s white paper, “A Framework for Making Successful Technology Decisions,” published in October 2020.

The focus of this white paper: electronic- and information-based systems that are being adopted now, are quickly developing, or are not really on the market yet, while keeping in mind that technology should allow an agency to do more at a larger scale in a way that supports the agency mission. By making good technology decisions, we want to end up with a set of systems that support and make transit either more efficient, more usable, or, ideally, both. Making decisions about when to add, remove, or update any technology can be daunting, but there are ways to make it more successful in the long run.

The white paper covers core concepts including capacity building and systems thinking as well as steps to take:

- Phase 1: Define and Rank Problems

- Phase 2: Develop Potential Solutions

- Phase 3: Procuring

- Phase 4: Implementation and Maintenance

Another resource that explains related topics in depth is N-CATT’s Guidebook on New Software Adoption for Small Transit Agencies, published in March 2021.

During the past decade, there has been a veritable explosion of software options that are available to small city/rural/tribal transit agencies to assist them in improving their operations and passenger interactions… There has never been a better time for a small transit agency to take advantage of software to help achieve its objectives and improve service to its customers… New software adoption has the potential to range from a relatively simple undertaking to an extremely complex one. This Guidebook provides a four-step process to move from the initial stages of software consideration to later steps involving set-up, operations, and maintenance.

The four-step process includes:

- Step 1: Set the Software Scope

- Step 2: Collaborate with the Software Stakeholders

- Step 3: Move Forward with a Software Product

- Step 4: Support the Software

While these two resources aid professionals in making technology decisions and help them go about adopting new software in general, the Guidebook on Digital Tools to Facilitate Complete Trip Planning deals specifically with technology and software that serves a particular purpose—trip planning for the complete trip. These resources will be referenced, when applicable, to guide professionals toward more detailed guidance on particular topics, allowing additional information below to be tailored to complete trip planning. A series of steps is proposed for the process of providing a digital tool for complete trip planning including:

- Step 1: Clarify challenges related to digital tools for the Complete Trip

- 1a. Set up stakeholder and project management roles

- 1b. Research and list digital challenges

- 1c. Evaluate and rank the challenges according to impact

- Step 2: Consider potential tactics to address digital challenges

- 2a. Research and list potential tactics

- 2b. Consider factors that impact tactic feasibility

- 2c. Evaluate and rank feasibility of the tactics

- Step 3: Plan for providing digital tools

- 3a. Consider what should happen in the next 10 years

- 3b. Identify supportive infrastructure needed for the next 10 years

- 3c. Confirm what will be done in the first 3 years and how it will be implemented

- Next steps

Note that the involvement of transit and mobility system users, including specific user groups such as individuals with disabilities, is a constant theme throughout the steps as shown in the following table.

| Step 1 | Transit and mobility system users should provide input on draft journey diagrams as well as on digital challenges they experience, or avoid, during specific journey segments. |

| Step 2 | Transit and mobility system users should provide input on potential tactics to address digital challenges. |

| Next Steps | Transit and mobility system users should provide input on the selection of digital tools (reviewing mock-ups and wireframes of specific tools that are being considered) and provide user feedback during the beta testing process. |

Step 1: Clarify challenges related to digital tools for the Complete Trip

Substep 1a. Set up stakeholder and project management roles

The Guidebook on New Software Adoption for Small Transit Agencies goes into significant detail in Chapter 2 / Step 2: “Collaborate with the Software Stakeholders” on how to identify all the relevant stakeholders (including end users) for a project, ways to actively involve them, and how to incorporate their feedback into decision-making processes. Chapter 1 of the Guidebook also mentions the need for a “software adoption lead” to help spearhead the effort; this person could also be referred to as a project manager. “The lead does not need to come from a software development or information technology background. The most important skill sets and knowledge the lead should have include transit operations knowledge, software benefits awareness, and organizational skills.” Early on to provide digital tools for complete trip planning, the full range of stakeholders, including the transit and mobility system users, should be identified; the person supporting the project management of the entire effort should also be clarified. Once this is complete, the effort will have its project team in place.

Substep 1b. Research and list digital challenges

First, draft customized “journey diagrams” for the local area.

To understand the types of challenges and gaps that people face when using digital tools for the Complete Trip, the project team should prepare to draft all the known and potential end-to-end journeys in the area as illustrated in Section 1.2. The mapping out of the journeys should have the input of the entire stakeholder group, including the transit and mobility system users, to ensure the set of end-to-end journeys is complete.

This input could be gained through both general public events and by holding smaller gatherings with representatives of specific user groups. Many transit agencies have advisory boards or committees, for example, some involving individuals with disabilities and older adults who provide feedback to the transit agency on an ongoing basis. The input of such groups could be sought to help create the journey diagrams. If a long list of journeys ends up being generated and is considered too unwieldy for discussion, 5-10 common journey types could be selected.

Then, identify digital challenges encountered during specific journeys.

Once the set of end-to-end journeys has been drafted and is considered complete by those involved, the project team and the user groups, the challenges can be identified through discussions and work sessions. It may also be worth considering online feedback options as shown through the “complete street upgrades” project in Westfield, Massachusetts. Each identified challenge should be located on a specific end-to-end journey and with the journey segments to which it applies. To better connect the Complete Trip segments with digital tools that are commonly used during each segment.

Again, the input would ideally be gained through both public events and by holding smaller gatherings with representatives of specific user groups. Some of the highlighted projects in this Guidebook provide examples of types of digital challenges to look out for such as:

- For multi/intermodal trips during trip planning: Trip planners missing entire modes such as demand-response transit, which leads to a fundamental lack of information on transit and mobility options.

- For demand-response transit trips during trip planning/booking: Customer difficulty in booking trips across multiple demand-response transit providers (without contacting each one separately), causing confusion about which one to contact first and what to do when a trip request is denied.

- For transit, cycling, and pedestrian trips during trip planning: Digital gaps in information about physical barriers impacting the feasibility of trips. These physical barriers could include inadequate bus stop conditions, missing bike lanes, or dangerous sidewalk conditions, for example.

Substep 1c. Evaluate and rank the challenges according to impact

Once a complete list of challenges has been generated, the challenges should be compared against each other as ”High”, ”Medium”, or ”Low” impact. While some challenges will have major impacts—presenting significant digital barriers—others will have relatively minor impacts. Making these assessments will be a subjective process involving the project team and user groups. For instance, in Substep 1b, “trip planners missing entire modes” will likely be seen as a High impact challenge. Another challenge example, “customer difficulty in booking trips across multiple demand-response transit providers” may be characterized as Medium or Low impact. It is frustrating for users, but overall may present less impact when compared to the other challenges in question. For this step, there are no right or wrong answers; the project team and user groups can discuss and debate these topics—using analytical tools for a more precise assessment as they see fit—eventually coming to agreement on how to characterize the challenges.

Step 2: Consider potential tactics to address digital challenges

Substep 2a. Research and list potential tactics

Once the challenges are confirmed, considerations can move toward identifying various tactics with the project team and the users providing input. Tactics are activities that could be undertaken to help address challenges, often focused on providing a specific tool or taking on a new initiative. For one challenge mentioned under Substep 1b, “trip planners missing entire modes,” different types of tactics could be proposed, for example. One tactic could be “make adaptations to the existing trip planner to enable all modes to be included.” Another tactic could be “provide a new trip planner that includes all modes.” For the challenge “digital gaps in information about physical barriers impacting the feasibility of trips,” tactics could be proposed such as “include barrier-related information within a new trip planner,” “adapt the existing trip planner to include barrier-related information,” or “setup a tool dedicated to providing barrier-related information, to be used along with a trip planner” as was done through the “bus stop accessibility map” project in Northwest Indiana. Tactics are highly context-dependent. Identifying them depends not only on the challenge they could help address, but also on the existing situation surrounding the potential tactic—the projects and initiatives that are, or are not, already in place that could help or hinder it.

Substep 2b. Consider factors that impact the level of effort for a tactic

There are various factors that can impact the level of effort of a tactic, making it much easier or more difficult to accomplish. For instance, for the potential tactics that should address the challenge “trip planners missing entire modes” which are “make adaptations to the existing trip planner to enable all modes to be included” and “provide a new trip planner that includes all modes,” more than likely both tactics would involve using GTFS-flex feeds in a trip planner, so that demand-response transit options (one of the missing modes) could be shown in the trip planner. If GTFS-flex feeds had already been created, then both/either of the tactics may involve less effort. If the GTFS-flex feeds had not been created, but one of the organizations on the project team offers one of their staff members to create the GTFS-flex feed, that would likely be easier than, for instance, going through the process of locating funding and procuring a tool/consulting services to create the data. Each situation regarding the status of getting GTFS-flex feeds ready presents information that makes the related tactic more or less effortless.

For this example, the GTFS-flex feeds are not the only input into the tactic. Another input to consider involves the status of the existing trip planner (if one exists); can it be adapted to add demand-response options, or would the difficulty of doing so contribute to considering another trip planner altogether? Is there even an existing product on the market than can include demand-response options, or would pursuing this tactic require the project team to create a custom software solution?

While the Guidebook Section 2.2 provides information on core topics pertinent to assessing the level of effort, a few more core topics are provided below:

· Considering existing software vs. creating new software

· Leveraging available resources

· Using the project table in Guidebook Section 2.3 as a state of the practice summary

When considering existing software vs. creating new software, there are several factors to consider. In the Guidebook on New Software Adoption for Small Transit Agencies, Chapter 3 goes into detail on this topic, “Small transit agencies today have a choice among multiple types of software products that address the same functional needs of the agency. These include commercial off the shelf (COTS) products, open source/public domain software, and custom software solutions. The advantages and disadvantages of each is discussed in this chapter.” In general, COTS products will be easier to set up, but they may potentially not have all the desired features and functions—and often, this cannot be changed. Custom software solutions typically require a very high level of effort to ensure that software consultants deliver a product that meets what the project team and end users have in mind. The “awesome-transit” list references a “community-maintained list” of “Entities Providing Transportation Software Development Consulting Services” (with an option to add new vendors).

Custom software solutions often need be hosted through a solution provided by the organization that is managing it, but COTS products are increasingly provided as Software as a Service (SaaS) projects. In short, there are several factors to consider related to how software options can influence the level of effort of a tactic. Explained in the Guidebook on New Software Adoption for Small Transit Agencies:

During the past decade, there has been a strong trend in business software in the direction of Software as a Service (SaaS) approaches. Among multiple advantages of a SaaS purchase, a major advantage for a small transit agency is that it does not have to concern itself with the computing infrastructure on which the software is hosted. This chapter discusses the relative merits of SaaS approaches compared to licensed software products that are hosted by the agency itself or for which the agency is directly responsible. For small transit agencies, software solutions that avoid the agency needing to be responsible for their own computing infrastructure are typically advantageous, assuming that broadband data access is available.

In some cases, available resources from among the project team can be leveraged to support efforts to provide digital tools for Complete Trip planning. The Guidebook on New Software Adoption for Small Transit Agencies provides information on this topic in Chapter 1, Step 1c. Anticipate Resources to Apply to Software Adoption, “Resources relevant to the software adoption process include (at a minimum) financial resources, staff resources, existing software and computing infrastructure assets, and collaborator resources—financial, staff resources, or assets from partner organizations. An agency should create an inventory of its likely available resources early to be prepared for later steps in the process.” Resources that could be particularly useful for complete trip-related efforts include existing data sets, software already in use that can be expanded, existing methods for centralizing data for multiple organizations, as well as in-kind financial and staff resources to help build and manage the work. If resources can be provided through a partner organization, instead of seeking out funding and going through a procurement process, then a tactic could become more feasible.

The Guidebook on New Software Adoption for Small Transit Agencies is a key reference for learning more about software options and the level of effort required for their success as well as how to pinpoint available resources from among the project team.

The project table in Guidebook Section 2.3 is also a key reference to better understand the potential effort level of tactics. Though not intended to be an exhaustive resource, the project table reflects the current state of the practice of digital tools for Complete Trip planning as of November 2021. When professionals are considering a certain tactic and are wondering if what they’d like to do has been done before, the project table could illuminate that question.

Substep 2c. Evaluate and rank the tactics according to level of effort

Once a complete list of tactics has been created, the tactics should be compared against each other as ”High”, ”Medium”, or ”Low” effort. While some tactics will be ”High” effort—representing a lot of work and effort—others will require relatively ”Low” effort. Making these assessments will be a subjective process involving the project team and user groups. For example, in Substep 2a, the tactic “include barrier-related information within a new trip planner” would likely be ”High” effort, but that would depend largely on if the trip planner already enables barrier-related information to be included (most do not), if data on barrier-related information already exists (it is difficult to collect), and what it would take to keep such datasets continually updated and accurate since barriers (e.g., deteriorating sidewalks and missing bike lanes) are constantly in flux. For this step, there are also no right or wrong answers; the project team and user groups can discuss and debate these topics—using analytical tools for a more precise assessment as they see fit—eventually coming to agreement on how to characterize the tactics.

Step 3: Plan for providing digital tools

Substep 3a. Consider what should happen in the next 10 years

First, plot the tactics according to the level of effort and impact.

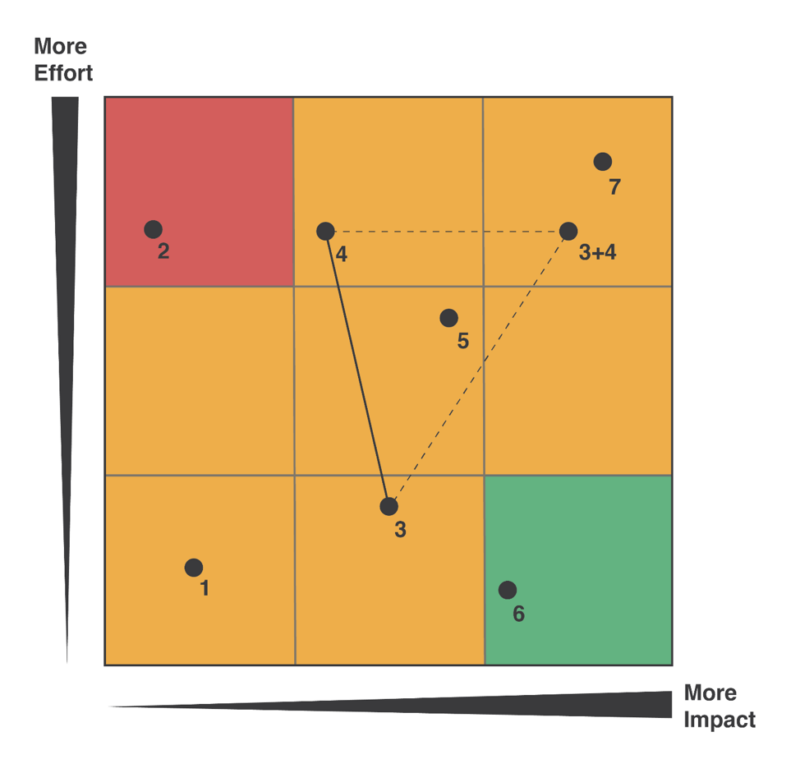

To gain a basic understanding of how the tactics compare, professionals should plot them as shown in the example of Figure 32. On the x-axis, the placement of the dot represents the challenge it seeks to address. The further to the right, the more impactful the challenge. The most impactful challenge, for example, would present an extremely significant barrier. On the y-axis, the placement of the dot represents the effort the tactic requires. The further toward the top, the more effortful the tactic. If a tactic has the potential to address multiple challenges, and its impact varies, estimate the combined impact of the challenges to plot the tactic on the table. In some cases, it can be difficult to consider tactics on a stand-alone basis because the tactics have the potential to reinforce each other—doing one could lay the groundwork for the other, or by combining them they can achieve much more impact than the sum of both. In these cases, a line can be drawn between the dots to show their potential for reinforcement. Further, if together their impact would change, a “ghosted” single tactic could be shown to represent their combined impact (keeping the effort level on par with the highest of the two unless the combination leads to a higher effort level) as shown in the figure below (points 3, 4, and 3+4). Once the comparison table has been plotted, it can be used as a planning aid.

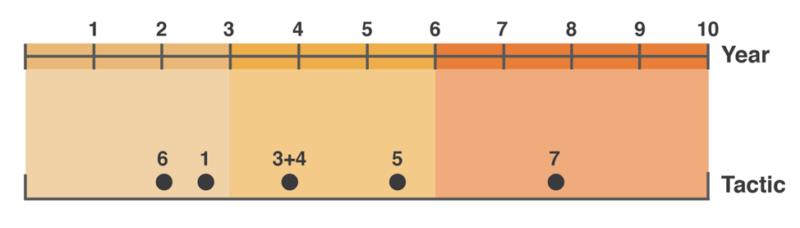

Then, add the tactics to the Complete Trip timeline.

Using the comparison table, a tentative 10-year timeline can be drafted. As shown below, of the nine sections, only one is green and one is red. The others are orange. The green section would encompass all the tactics that are High impact and Low effort; in general, these tactics would make sense to implement. The red section would encompass all the tactics that are Low impact and High effort; in general, it would not make sense to implement these tactics. The interpretation of the remaining seven sections, in orange, is at the discretion of each project team. For example, some teams might find tactics that are in the middle of the table, those that are Medium impact and Medium effort, reasonable to pursue; other project teams may see this very differently. Tactics that are High impact and High effort may make sense to pursue, at least in the longer term, since they can address major barriers. Tactics that are Low impact, regardless of if their effort level is Low or Medium should be assessed individually to decide if they are worth pursuing—even low effort tactics can reduce the overall bandwidth to take on more impactful and important efforts.

Each tactic should be added to the timeline as shown in the example in Figure 33. Those in the green section would typically be placed in the early years of the timeline, while those in the red section would be removed. The tactics in the orange section can be placed on the timeline, relative to an estimate of when they could be completed; they can also be removed at the discretion of the project team. The timeline is a simple approximation of what should happen when—representing basic draft ideas. Notes can be included and lines can be drawn between the tactics to help add on additional layers of information the project team finds helpful.

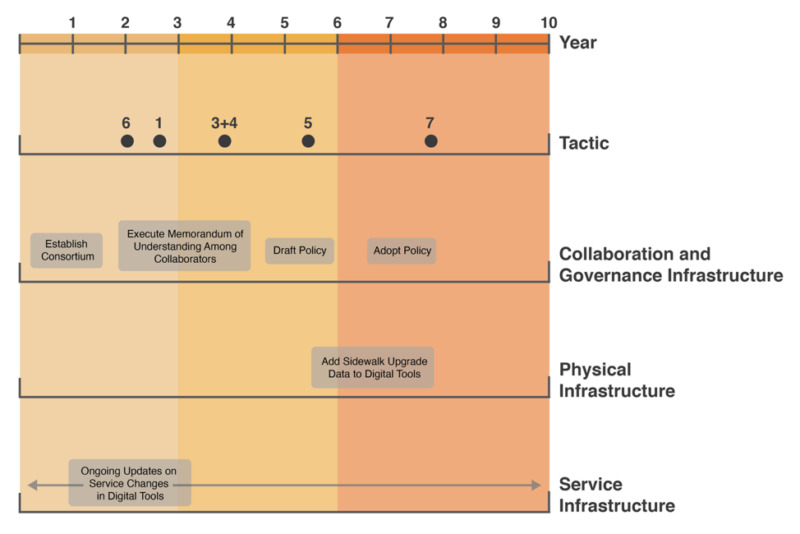

Substep 3b. Identify supportive infrastructure needed for the next 10 years

After Substep 3a is complete, it is time for the project team to look at the big picture and consider the supportive infrastructure—the physical, service, and governance infrastructure—that will be needed not only for separate tactics but for the effort as a whole. Each infrastructure element should be added generally where it is likely needed within the overall time frame; for example, perhaps some elements should be up and running prior to a certain tactic being implemented. It is typical that an infrastructure element could support multiple tactics at once. If helpful, the tactic numbers can be noted beside the infrastructure elements to keep them connected.

Substep 3c. Confirm what will be done in the first 3 years and how it will be implemented

First, establish the general direction of the first three years through exploratory questions.

Substeps 3a and 3b helped generate a rough idea of what the effort might include over the ten-year horizon. At this point in the planning process, a closer look is called for into the first three years. The draft generated during Substeps 3a and 3b should be used as a start, but the project team can look at this more closely for the near-term effort. To decide if the tactics and supportive infrastructure listed are what should be pursued, the project team should consider the following questions:

- What is the reinforcement potential for the tactics listed for the first 3 years? The reinforcement potential refers to the way the tactics build upon each other to have a more significant impact as a set rather than separately. If the reinforcement potential is Low, but that is true for most/all of the tactics, that means the tactics are largely stand-alone tactics. If the reinforcement potential is Low, but moving a few years out on the timeline starts to gain some traction, it may be worth detailing the tactics on a five-year basis instead of three years—that would still be in the near term while allowing for some benefits of combining the efforts. By the end of discussing and debating this question, the project team should have agreed to keep the tactics as shown or revise them, including revising the time horizon as needed for the near term (around three to five years).

- Once the tactics have been agreed upon, are all the supportive infrastructure elements that are needed included in the draft for the agreed upon time horizon? If not, but the elements are included in the timeline at a later point in time, then they can slide over to an earlier time in the near term. If not, but the elements are not included in the draft at all, they should be added. At the end of this discussion, the project team should determine the supportive infrastructure elements that will be needed for the near term.

Then, establish the specifics for the first three years through a project management plan.

After the previous discussions have confirmed “what” will be done, the question becomes “how” will it be done? This will generally involve sorting through the issues of who to involve, the roles each organization/individual will have, what tasks and subtasks need to be completed, and when certain milestones should be met. The person supporting the project management role would help guide the project team in creating a project management plan, which could be created in excel or a software specifically designed for task and project management. If a procurement process is required, a set of procurement tasks would be included within the plan. More details on this can be found in N-CATT’s “Procurement Playbook.” Creating a realistic and well-detailed project management plan is a major task, and the project team may need to gather additional information to be able to compete it.

For background reading on “how to move forward with a software product” see chapter 3 of the Guidebook on New Software Adoption for Small Transit Agencies which includes a “series of 7 steps that need to be navigated from the time when the agency decides it wishes to acquire new software until the point when the software becomes operational for the agency, enabling them to move forward with a software product.” These steps include:

- Step 3a. Determine What Type of Software Your Agency Needs

- Step 3b. Understand Your Available Software Choices

- Step 3c. Determine Whether to Obtain a SaaS System or a Licensed Software Product

- Step 3d. Determine Your Core Requirements for the Software

- Step 3e. Develop the Request for Proposals

- Step 3f. Evaluate the Proposals and Select the Most Appropriate Software Product

- Step 3g. Begin the Software Implementation Process

For additional reading on how to “support the software,” see Chapter 4 of the same resource. The steps include:

- Step 4a. Plan for One-Time Software Setup and Training

- Step 4b. Prepare for Ongoing Support Needs

- Step 4c. Consider Additional Support as the Software Scope Expands

Once the roles, tasks, and milestones are clear for the time horizon (typically 3-5 years), implementation can begin.

Next Steps

After Step 3 has been completed, implementation can begin by following the project management plan for the time horizon specified. Throughout the implementation process, the project team should consider any major changes that affect the effort and adjust plans as necessary. It is important to make sure the project management plan includes user involvement activities that will take place during the implementation process as well. This would largely be focused on two efforts; the first would be gaining input on the selection of digital tools, reviewing mock-ups and wireframes of specific tools that are being considered, for example, to narrow in on products that would address the challenges adequately. Second, they would provide user feedback during the beta testing process; such an activity would result in identifying the details of the digital tool that need refinement to make the public release of the tool ready for prime time.

Since the overall effort is designed with a ten-year horizon in mind, at some point the project team may be ready for the next phase of the effort, for example moving from years 1-3 to years 4-6. The planning for “phase 2” can even begin during the implementation of Phase 1. When the project planning work begins for Phase 2, the draft materials from Substeps 3a and 3b can be used as a starting point. Many of the inputs and details would likely have changed, so significant revisions are probably required. Nonetheless, Substeps 3a and 3b provide a starting point, and if the project team is still comprised of most of the same members, the institutional knowledge—based on the group having completed this exercise before—will be very helpful.